FIRST EDITION

Codin Alexander Olteanu

Ideas of Power and the Power of Ideas: Alignment, Application, Adaptation, Articulation in Jomini’s and Clausewitz’ Studies of Strategy

Abstract

The concept of ‘strategy’ is making a remarkable comeback in the 21st century, as balance-of-power politics is being played again, this time truly at the global level. This essay investigates the genesis of ‘Strategy with a capital “S”’ in the writings of Jomini and Clausewitz in the first half of the nineteenth century and the dynamics of its theoretical interpretation and practical application from the Napoleonic Era to today. It does so by applying the ‘4 As’ of interpretive hermeneutics – prefigurative Alignment, configurative Application, refigurative Adaptation and transformative Articulation – to this iterative investigation of Jomini’s and Clausewitz’s work. This methodology results in the emergence, from the interstices of their competing and complementary approaches to War and Strategy, of a three-dimensional concept of ‘Strategy’ aligning Policy Process, Power Praxis and Political Purpose. It also gives rise to a corresponding analytical framework of the deployment of ‘Strategy’ in various spatio-temporal environments, that combines various leadership modalities with a full continuum of conflictual systems. This essay concludes by arguing that both these elements of the Strategy-as-practice toolkit remain remarkably current and eminently applicable to the rapidly evolving geopolitical ecosystem of the 21st century.

Keywords:Strategy; Tactics; Total War; Warfare;Enlightenment;Romanticism; Dialectics; Nuclear Era; Napoleon; Frederick II; Clausewitz; Jomini; Guibert; Hermeneutics.

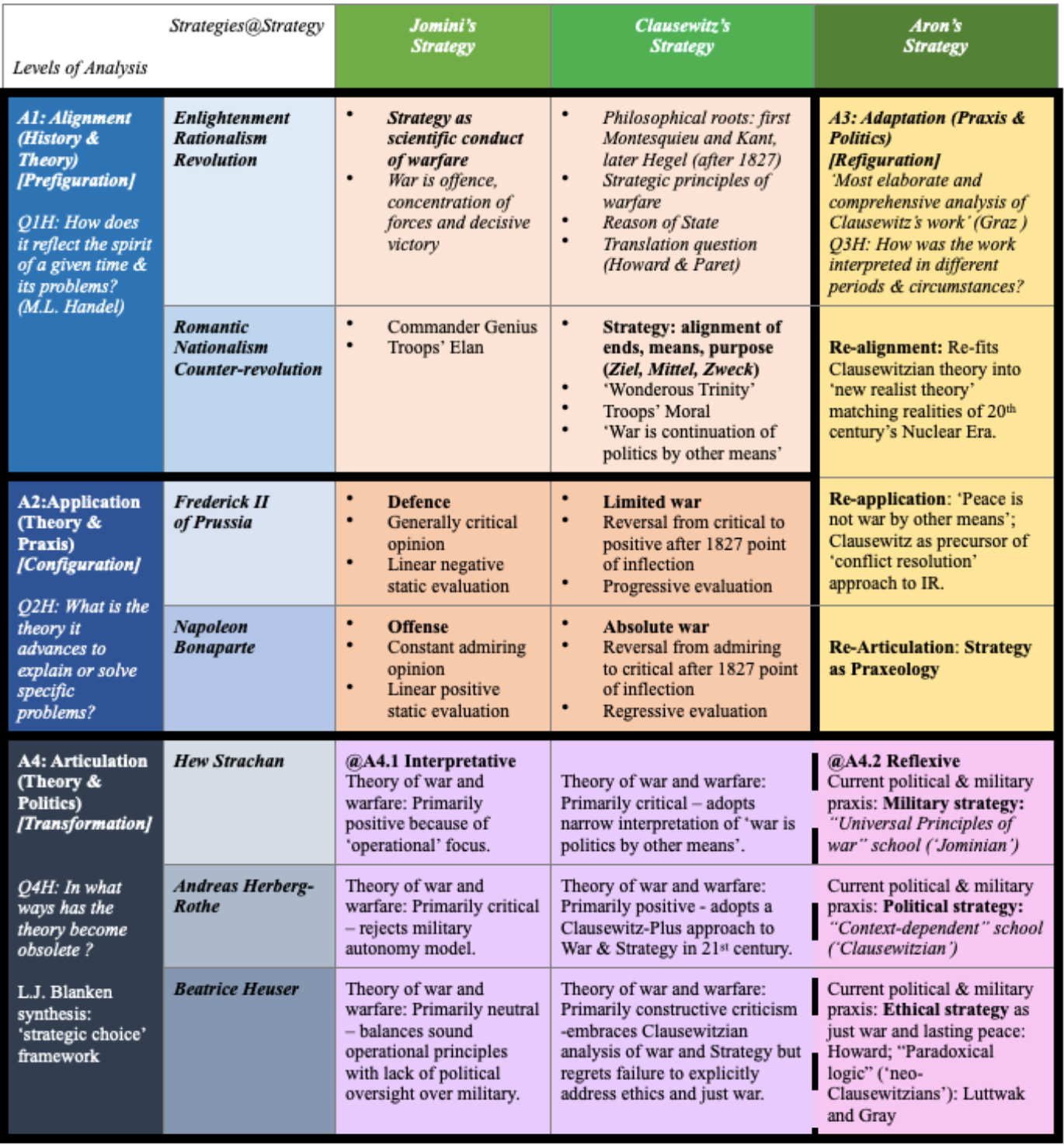

The 4 A’s of Interpretice Hermeneutics

How best to begin an inquiry into whether Jomini and Clausewitz ‘wrote about strategy’? Do we, like Heuser (2010b: 3), apply to them retrospectively our own definition of “Strategy with a capital ‘S’”– knowing that our current Transatlantic understanding thereof primarily reflects the latter’s conceptualization rather than the former’s? Do we stick to their original texts and focus on their definitions of ‘strategy’, as Strachan (2007: 24) seems to advise? Or does an “adequate treatment” of the two giants of modern strategic thought entail that we attempt, with Herberg-Rothe (2007a: 306-307), to think both “with” and “beyond” them? Four decades ago, Aron (1976) had already explained that each such point of view constitutes a separate interpretative level and Lefort (1977: 1269) had approvingly commented that each such hermeneutic circle adds a necessary and necessarily critical perspective to a coherent and comprehensive assessment of the original question.

We have entered the third decade of the 21st century – a time when the notion of ‘strategy’ is experiencing an unexpected regain in popularity. Old regional and global frameworks of governance seem to fade away whilst 19th century Europe’s ‘Great Game’ of ‘balance of power competition’ (Kissinger, 1994) is being played again, only this time on a ‘Grand Chessboard’ at the planetary level (Brzezinski, 1997) and “[w]ith GPS” (Gray, 1999a). It is therefore more important than ever that we come to terms with what “Strategy with a capital ‘S’” means to us today.

Strategy as Alignment

The first dialectic circle of interpretative hermeneutics as elaborated by Aron and Lefort consists of prefiguring how Jomini’s and Clausewitz’s substantive theoretical frameworks align with the historical contexts of their socio- cultural ecosystem. It thereby provides an answer to the first of Handel’s (1986: 4) four key questions in light of which any great work of political theory must be analysed – namely, the manner in which it reflects “the spirit of a given time and its problems”.

The three-quarters of a century spanning Frederick II’s invasion of Silesia, in 1740, and Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, in 1815, constitutes a period of almost incessant warfare in European history. This era of upheaval and conflict marks three important interdependent transitions that reshaped the destines of the Old Continent and of the entire world: from Enlightenment Rationalism to Romantic Nationalism (Gat, 1992: 1-2; Calhoun, 2011; Niebisch, 2011); from limited ‘Wars of Princes’ to total ‘Wars of Nations’ (Hagemann, 2015: 136); and from an almost exclusive preoccupation with the scientific study of the specific principles of warfare to a philosophically-anchored investigation of the full complexities of war (Herberg-Rothe, 2001; 2009). Colin Gray best explains this critical distinction when he states that:

“War is a relationship between belligerents; it is the whole context for warfare. Warfare is defined as ‘the act of making war’”. (2006: 82)

The concept of Strategy emerged and developed i n the interstices of the tension between the theory and practice of ‘war’ and ‘warfare’ and is critically shaped by all three transitions mentioned above. The two catalysts for Strategy’s rise as the primary practice connecting the emerging European national states’ networks of power – political, military, diplomatic, legal, and civic – were Prussia’s Frederick the Great (1712-1786) (von Hohenzollern, 1999; Kunnisch, 2005) and France’s Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) (Bonaparte, 1999; Colson, 2015). Although neither ruler used the word ‘Strategy’ as such whilst in power, they were its greatest practitioners and served as inspiration for the three individuals who together defined and clarified the meaning and importance of Strategy during this era: the French Comte de Guibert (1743-1790) (Chaliand, 1994; Heuser, 2010d), the Swiss Antoine-Henri Jomini (1779- 1869) (Howard, 1965; Shy, 1998) and the Prussian Carl von Clausewitz (1780-1831) (Parkinson, 1970; Paret, 1976).

De Guibert first defined strategy in his ‘Essai général de la tactique’ as “the entire art of movement or large-scale army manoeuvres”, within an emerging vision of unlimited war of movement of massive ‘citizens’ armies’ (Bonaparte, 1999; Colson, 2015). Jomini followed suit concentrating on the operational level by dividing “the art of war” in five “purely military” branches – Strategy, Grand Tactics, Logistics, Engineering, and Tactics – and describing ‘strategy’ as “the art of properly directing masses upon the theatre of war, either for defense or for invasion” (2007: 7). For Clausewitz, “the distinction between tactics and strategy is now almost universal… [T]actics teaches the use of armed forces in the engagement; strategy, the use of engagements for the object of war” (1976: 128). Critically, for him, the object of war can only be politically determined, hence his famous statement that “war is not merely an act of policy but a true political instrument, a continuation of political intercourse, carried on with other means” (1976: 87).

Although both Jomini and Clausewitz focus on the operational level of warfare when defining ‘strategy’ (Strachan, 2011) and each develops a set of applicable principles (Strachan, 2007: 83) in the conduct of ‘engagements’, the objectives of their studies are radically different (Aron 1976). Jomini aims to establish the scientific nature of warfare by devising a set of universally applicable principles. These tenets must be, in his view, free of political control and capable of being deployed in practice by the military commander’s ‘genius’ irrespective of time, place or technological change (Niebisch, 2011). Conversely, Clausewitz rejects this approach (Paret, 1976: 153) because he realises that “there is more to war than warfare” (Gray, 2006: 86). Therefore, he focuses first on the nonlinear contingencies (Beyerchen, 1992), interactive uncertainties and risk probabilities (Waldman, 2010) of war and on the need to constantly adapt its practice to specific spatio-temporal contexts (Fleming, 2009; Drohan, 2011). Secondly, he emphasizes that political aims constitute war’s very reason for being deployed to either threaten one’s adversary or to physically submit it to one’s will (Schuurman, 2014; Milburn, 2018).

Strategy as Application

The second dialectic circle of interpretative hermeneutics resides in configuring how Jomini’s and Clausewitz’s theoretical systems apply to the key practical examples they deploy to substantiate their main tenets – in our case, to the strategic praxis of Frederick II and of Napoleon, both instrumental in substantiating the strategies and principles of warfare advanced by our two authors (Luvaas, 1986; Shy, 1988). It thus addresses Handel’s second interrogation regarding works of political philosophy, focusing on the substance of the theory designed to “explain or solve specific contemporary problems” (Handel, 1986: 4).

Both Jomini and Clausewitz used the ‘vicarious experience method’ (1986: 18) in their dialogue with their ‘two great captains’ – Frederick and Napoleon (1986: 18-19). Jomini first studied Frederick’s battles to develop his principles of warfare, then adapted them to Napoleon’s strategy in combat (Gat, 1989). He then criticized Frederick for often failing to implement his principles by being overly timid (Gat, 1989: 122) and eventually Napoleon for forgetting “that the mind and strength of man have their limit” (Handel, 2005: 272). In doing so he aimed to establish the scientific universality of his principles of warfare – an aim which remained virtually unchanged throughout his long life (Shy, 1998: 145). Clausewitz deployed in addition a ‘critical analysis’ method’ (Handel, 1986: 19) to the study of Frederick and Napoleon by means of a dialectical “application of theoretical truths to actual events” (Bonaparte, 1999: 141). He went far beyond Jomini’s ‘manual of warfare’ containing static principles of operational strategy by positing that strategy varies with the nature of the war being conducted and with its ultimate political purpose (Heuser, 2002). Clausewitz thus succeeded in devising a conceptual framework of war as a system capable of accommodating both Frederick’s limited war practice and Napoleon’s ‘total war’ approach” (Bonaparte, 1999; Esdaile, 2008). Human knowledge develops in specific socio- historical contexts, through dialectical exchanges of views between members of interconnected multi-generational intellectual clusters, each of whom attempts to occupy the central nodal role of his cluster in terms of reputation and influence as well as of career and personal benefits (Collins, 1998). Such a cluster developed in Europe with respect to the study of war and strategy from the 1740s to the 1840s. Pioneering authors such as Henry Lloyd (1718-1783) (Howard, 1965: 6-8), Dietrich von Bülow (1757-1807) (Palmer, 1998) and the Archduke Charles of Austria (1741-1847) (Heuser, 2010b) were supplanted by a remarkable trio: Guibert set the terms of a new approach to Strategy in 1772 (Chaliand, 1994; Heuser, 2010b: 18-19); Jomini articulated his Principles of Warfare and published them in 1804 (Gat, 1989); Clausewitz read Jomini’s initial work, criticized it (Gat, 1989: 123-124) but also re-interpreted and re-defined, after 1827, his own way of thinking about War and Strategy (1989). Finally, Jomini studied Clausewitz’s On War, first printed in 1832, then used it to adapt and modify his own seminal work, The Art of War, published in 1838 (Shy, 1998: 153-155). It is this creative tension and iterative dialectical development (Howard, 1965: 10) that have bequeathed us not only a three-dimensional concept of ‘Strategy’ aligning Policy Process, Power Praxis and Political Purpose (von Clausewitz, 1976: 372; Strachan, 2013: 58), but also a corresponding analytical framework of its deployment in various specific spatio-temporal environments. Both of these remain remarkably current to this day and are fully mapped out here for the very first time.

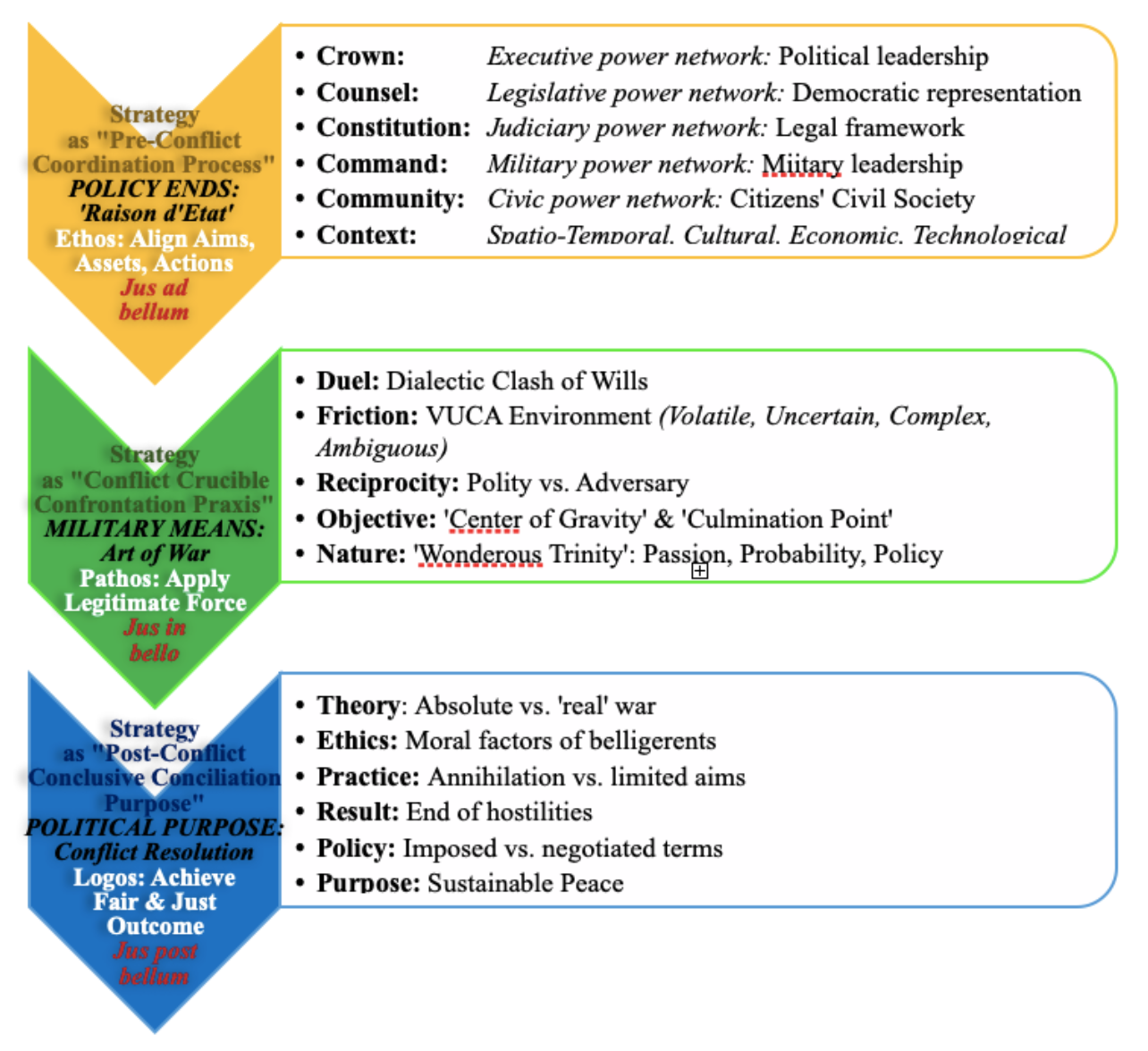

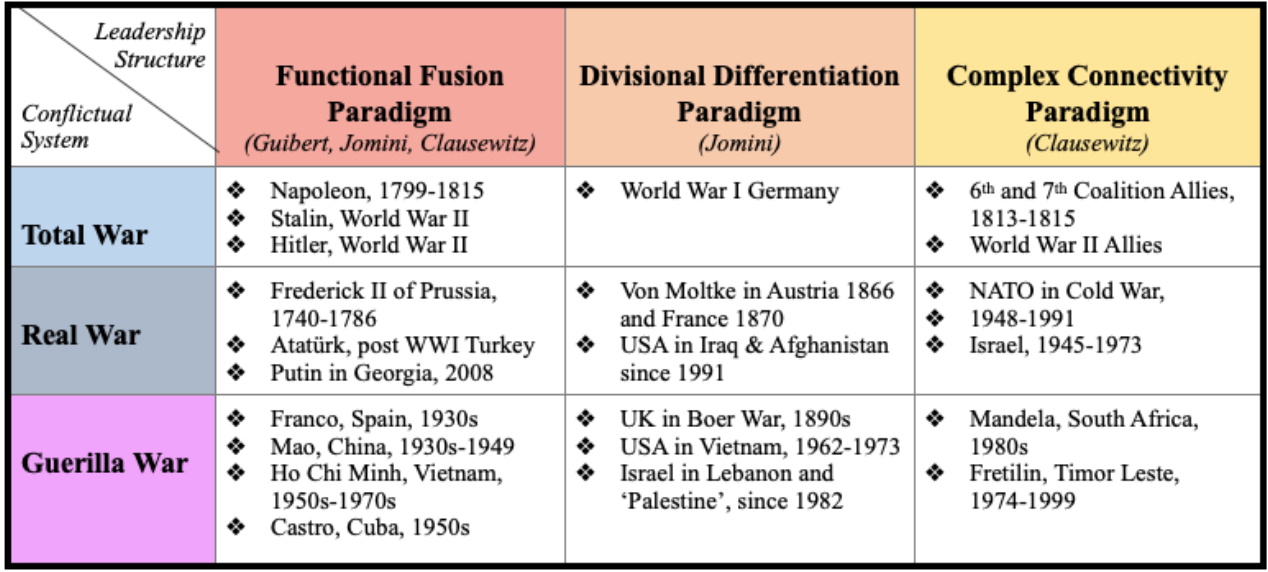

‘Strategy’ thus came to encompass a new “amazing Trinity” (Howard, 2007: vii) connecting the Process, Praxis and Purpose of War. First, it refers to the iterative Process of aligning the aims, assets, and actions of a polity’s sovereign Crown, political Counsel, legal Constitution, military Command and civic Community networks active within a specific dynamic spatio- temporal, cultural, economic and technological Context (jus ad bellum). Second, it imposes in actual Praxis, through a dialectical confrontational clash of wills carried out in a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous crucible of conflict (Mackay, 2020), that polity’s objectives upon its adversary(ies) by means of applying the threat or use of legitimate force (jus in bello). Third, it does so for the conclusive Purpose of achieving a fair and just outcome for all participating parties, resulting in the contestants’ conciliation and ultimately in a sustainable peace (jus post bellum)” (see Fig. 2). The analytical framework mapped out by this definition encompasses three ‘ideal’ paradigms of Grand Strategy (Wallach, 1986: 302-303), differentiated by the alignment dynamics between Crown, Counsel, Constitution, Command, Community and Context: the primary Functional Fusion Paradigm (Luvaas, 1986: 167; Gray, 1999b: 77-78) to which Guibert, Jomini and Clausewitz all contributed; the Jominian Divisional Differentiation Paradigm (Shy, 1998; Strachan, 2013); and the Clausewitzian Complex Connexity Paradigm (von Clausewitz, 1976: 130). In ‘reality’, each polity structures its own type of Grand Strategy during specific historical eras. The substantive content and subjective interpretation memorialising the past, analysing the present and pointing towards the future (Strachan, 2013: 235) of such Grand Strategies are defined by the interaction between the type of leadership structure and nature of conflictual system deployed in each particular circumstance. This double continuum, already prefigured in Clausewitz’s writings (1976: 378-379), succeeds in connecting the ‘Fusion’, ‘Differentiation’ and ‘Connectivity’ leadership modalities on the one hand, with the ‘Total’, ‘Real’ and ‘Guerrilla’ warfare (Strachan, 2013: 62) conflictual systems on the other, within an overall conflict classification matrix (see Fig. 3 ).

Figure 2: Clausewitzian System of Grand Strategy-as-Practice

Figure 3: Classification of Wars in the Guibert/ Jomini/Clausewitz Conflict Ecosystem

Whereas only the Strategy variations encompassed by the ‘Complex Connectivity Paradigm’ correspond to our current Transatlantic theoretical understanding of the proper relationship between military power and civilian politics (Herberg-Rothe, 2008; 2014; 2016), this analytical framework maps out for explanatory purposes all other options deployed by various state and non-state actors over the past two centuries, without evaluating them from normative or practical perspectives. By deploying this definition and analytical framework of Strategy, we gain a much clearer perspective of the evolution of the notion and application of Strategy from the mid-18th century onwards. This helps us to master both the philosophical and historical tools enabling us to assess their deployment in specific spatio- temporal contexts. We also come to appreciate why Frederick’s and Napoleon’s Fusion Paradigm was replaced by Jomini’s Divisional Differentiation Paradigm after 1815 (Harsh, 1974; Shy, 1998; Dighton, 2018), why the latter turn began to be supplanted by 1870 by Clausewitz’s Complex Connexity Paradigm (Heuser, 2007; Schuurman, 2014; Binkely, 2016) – and why all three re-emerged at various historical conjonctures across the 20th and 21st centuries in multiple forms and variations (Griffin, 2014; Hench, 2017; Johnson, 2017; Hughes and Koutsoukis, 2019). It is in this sense that Paret aptly observed that:

“[w]ith an efficiency that never ceases to be impressive, each generation chooses those features of an idea [of Strategy] that seem immediately useful, while disregarding or even falsifying the total intellectual concept from which they stem”. (Howard, 1965: 23)

Strategy as Adaptation

The third dialectic circle of interpretative hermeneutics posits that an interpreter of Jomini’s and Clausewitz’s texts active in a different spatio-temporal setting –in our case, 20th-century French philosopher Raymond Aron who in his seminal book Penser la guerre, Clausewitz, published in 1976 (Aron, 1976), “offers the most comprehensive and elaborate analysis of Clausewitz’s work and theoretical conceptions” (Gat, 1989: 170) – attempted to refigure their works in such a way as to adapt their historically-bound praxis to his own distinctive political environment. It thus proposes a reply to Handel’s (1986: 4) third seminal question regarding great works of political philosophy, namely in which ways it was “interpreted in different periods and circumstances”.

In contrast to B.H. Liddell Hart (Beaufre, 1965; Strachan, 2013: 126-127), whom he criticizes for a superficial reading of Clausewitz (Aron, 1976), Aron focuses on the Prussian’s post-1827 reworking of On War and on his two Notes (Aron, 1974; Lefort, 1977). Like Hart, Aron develops an ‘indirect’ strategy of armed conflict (Aron & Tenenbaum, 1972: 599-621; Emmanuel, 1986: 248-268), but one based on the Clausewitzian insight that the threat of war deployed for policy purposes in order to avoid an actual clash of arms often constitutes the most effective available strategic option. The French author aims to distil therefrom a new strategy of war capable of avoiding direct military confrontation, that best explains the ‘cold war’ of the bipolar nuclear world in which he lives (Aron, 1976: 139- 183; Freund, 1976: 643-651). He analyses Clausewitz’s and Jomini’s approaches to war by defining the central debate opposing them as the existence of a universal “key to the science of war […] a theory capable of revealing to military leaders the secret of victory” (Aron, 1976: 282). He then deploys the use the two authors make of Frederick II and Napoleon’s campaigns (Aron, 1976: 446-450) to demonstrate that Jomini not only failed to fully grasp the “solidarity between politics and strategy” which excludes “the autonomy of the military conduct of operations” (Aron, 1976: 282-283), but was also unable to envisage the topic central to Clausewitz’s entire work: the relationship between concepts and history (Aron, 1976: 283). Aron shows that whilst Jomini proclaimed that the fundamental principles of strategy remain the same and unchanged for all times because they are “independent of the nature of the weapons and organisations of hosts” (Aron, 1976), Clausewitz wrote that “each epoch develops its own strategic doctrine” (Aron, 1976; Luvaas, 1986, 168). Aron goes on to elaborate a concept of nuclear deterrence based on Clausewitz’s insight of war as an instrument of politics and derives therefrom a theory of peaceful conflict management as the highest form of strategy (Cozette, 2004; Cooper, 2011), one uniquely suited for an international community defined by a limited sovereignty of states resulting from the real threat of total nuclear annihilation (Arndt, 1977).

Strategy as Articulation

The fourth dialectic circle of interpretative hermeneutics asserts that contemporary critics of both Jomini’s and Clausewitz’s work and of their earlier interpreters’ application of the two theorists of war’s writings to their own era will perform a transformative task of double articulation. First, they will engage in an interpretative articulation effort aimed at elucidating Jomini’s and Clausewitz’s original texts on their own terms and in their specific contexts based on the totality of the information pertaining thereto currently available. Second, the critics in question will undertake a reflexive articulation exercise of “refracting” (Barkawi and Brighton, 2011: 535-536; Neibisch, 2011: 260) these interpretations through the adaptation lenses of earlier commentators, such as Aron.

This will inform the latest critics’ aim of distilling a new and relevant conceptualisation of the original texts, capable of providing meaningful insights for current theoretical understandings and future practical actions. This methodology corresponds to Handel’s (1986: 4) fourth key question regarding a work of political philosophy, namely “[i]n what ways has the theory become obsolete” and to its logical corollary, focusing on the work’s internal resources to overcome obsolescence and remain relevant when applied to contemporary spatio-temporal ecosystems.

We will briefly touch here on three well-known experts of ‘Strategy’ in general and of the ‘Napoleonic war paradigm’ in particular: Hew Strachan, Andreas Herberg-Rothe and Beatrice Heuser. All three authors wrote influential monographs analysing Clausewitz’s On War (Heuser, 2002; Herberg-Rothe, 2007b; Strachan, 2007), made important contributions to the insightful 2007 book entitled Clausewitz in the 21st Century (Strachan and Herberg-Rothe, 2007) and critically addressed various aspects of Raymond Aron’s commentaries on Jomini and Clausewitz (Herberg-Rothe, 2007a: 306-307; Strachan, 2007: 24; Heuser, 2010b: 3).

Strachan takes a Jominian ‘military strategy’ approach (2007) by defining strategy in terms of ‘universal principles of war’ (2005; 2011; 2019). He believes Clausewitz’s late insight on the relationship between war and policy has been overemphasized (2013: 13; 2007: 96-97) and disagrees with Aron’s attempt to integrate his writings into the theory of a peaceful liberal international order (Herberg-Rothe, 2007: 306- 307). Herberg-Rothe adopts a very different, context-dependent ‘political strategy’ approach (2001; 2007b; 2014) leading him, like Aron, to make a direct connection between Clausewitz’s late notion of ‘limited war’ and the emergence of a states’ system capable of progressively limiting war and violence for its own self-preservation (2007a; 2008; 2016).

The third school of thought comprises scholars who analyse Clausewitz’s thoughts on the ethics of war from complementary angles. Colin Gray believes that grand strategy is a process that serves as a “bridge relating military power to political purpose” (2006: 1) and that “history’s strategic winners, are the ones who decide what is just and what is not” (1999b: 55). Edward Luttwak focuses primarily on operational strategy’s “paradoxical logic” (2001: 3) aiming to suspend, however briefly, the opponent’s capacity to react effectively by successfully deploying the element of surprise (2001: 4). Heuser shares Gray’s and Luttwak’s commitment to Clausewitz’s continuing relevance as a strategist of war (2007; 2010c). However, she goes beyond them by drawing on Michael Howard’s work (Howard, 1967) to identify throughout the Prussian’s entire oeuvre an immanent concern with an ethical foundation for strategic action (Heuser, 2007), capable of being fruitfully rearticulated for the contingencies of the 21st century (Heuser, 2020). Like Clausewitz, Heuser deploys a dialectical critical analysis of history (2001; 2002) to develop a theoretical perspective of the ‘ideal’ ethics of war. She then nuances her approach in light of war’s realities (Heuser, 2010a; 2010b; 2018), so as to ultimately arrive at a dynamic concept of ‘ethical strategy’ (Mattox, 2008; Heuser, 2013) inhabiting this continuum connecting a universal ‘ideal’ and a context- dependent ‘reality’. Leo Blanken deploys this insight to deny the incompatibility of the three schools of thought outlined here and to integrate them into an overarching framework of “strategic choice” providing “a more transparent method for choosing among strategies” (Blanken, 2012).

Jomini’s And Clausewitz’ Enduring Double Dialectics On War And Strategy

Clausewitz’s enduring double breakthrough was first to recognise that social and institutional change happens dialectically and second to apply this insight to his study of war in general and of ‘Strategy’ in particular. Anticipating Thomas Mann’s central thesis in ‘The Magic Mountain’ (Mann, 1969: 726-727) by a century, he intuited that dialectical change is not deterministically unidirectional and progressive, but radically open-ended and multi- directional – and can therefore be regressive as well. Clausewitz’s and Jomini’s attempts to come to terms with the meaning of ‘Strategy’ were and continue to be shaped by a double dialectic: first, an ever-evolving internal tension between their two contrasting visions of the theoretical meaning and practical application of the term; and second, a shifting binomial pairing reversing its polarity both positively and negatively with each successive external historical and interpretative iteration. It is out of this double- dialectic dynamic connecting internal conceptual epistemology and external systemic ontology unfolding over the course of the past two centuries that our own understanding of ‘Strategy’ has emerged and continues to evolve in the rapidly-changing ecosystem of the 21st century.

Clausewitz’s and Jomini’s texts discussing the practice of Strategy in times of conflict thus take pride of place in an uninterrupted line of disquisitions going back to Plato and Cicero (Heuser, 2010b: 44-45; Freedman, 2013: 38-40), all of which have as ultimate aim to answer a timeless and universal question, retaining its actuality to this day. This question was best articulated by Michael Howard half-a-century ago: “Under what circumstances can armed force be used, in the only way in which it can be legitimate to use it, to ensure a lasting and stable peace?” (Howard, 1967: 64-65). As Beatrice Heuser reminds us in her Evolution of Strategy (2010b: 45; 2020), the essence of this answer was already outlined exactly two millennia ago by influential first-century A.D. Greek philosopher Onasander, as he summed up his treatise, Strategikos (The General). He did so by incisively describing the ideal Strategist (Chaliand, 1994: 154-156) in a manner entirely consistent with Clausewitz’s view on the matter, as someone capable of effectively combining the human soul’s ‘amazing Trinity’ (Howard, 2007: vii) – ethos, logos, pathos – with an ethical vision of eudaimonia – a virtuous life well lived (Stricker, 1987: 183):

“[…] a good man, then, will be not only a brave defender of his country and a competent leader of an army but also for the permanent protection of his own reputation will be a sagacious strategist”. (Chlup, 2014: 57)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aldama, L.A. (1978) ‘Review – Penser la guerre, Clausewitz by Raymond Aron’, Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 4 (Oct.- Dec. 1978), 199-204.Alish, H. (2013) ‘Rezension – L. Souchon (2012) Carl von Clausewitz und Strategie im 21. Jahrhundert. Hamburg, Mittler & Sohn Verlag’, Z. Aussen Sicherheitspolitik 6 (2013), 299-300.

Arndt, H. (1977) ‘Bleiben die Staaten die Herren der Kriege? Zum Clausewitz-Buch von Raymond Aron’, Der Staat 16 (2), 229-238.

Aron, R. (1974) ‘Clausewitz’s Conceptual System’, Armed Forces and Society 1 (1), 49-59.

Aron, R. (1976) Penser la guerre, Clausewitz (2 vols). Paris, Gallimard. Aron, R. and Tenenbaum, S. (1972) ‘Reason, passion and power in the thought of Clausewitz’, Social Research 39 (4), 599-621.

Aron, R. (1977) ‘”Clausewitz and the State” by Paret’, Annales. Histories, Sciences Sociales 32 (6), 1255-67.

Beyerchen, A. (1992) ‘Clausewitz, Non-linearity, and the Unpredictability of War’, International Security 17 (3), 59-90.

Beyerchen A. (2007) ‘Clausewitz and the Non-Linear Nature of War: Systems of Organized Complexity’, in H. Strachan and A. Herberg- Rothe, eds., Clausewitz in the 21st Century. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Blanken, L.J. (2012) ‘Reconciling strategic studies … with itself: a common framework for choosing among strategies’, Defense & Security Analysis, 28 (4), 275-87.

Bonaparte, N. (1999) Napoleon on the Art of War, trs. & ed. by J. Luvaas. New York: Free Press.

Brodie, B. (1989) ‘A Guide to the Reading of “On War”’, in C. von Clausewitz, On War, trs. by P. Paret and M. Howard, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Binkely, J. (2016) ‘Clausewitz and Subjective Civilian Control: An Analysis of Clausewitz’s Views on the Role of the Military Advisor in the Development of National Policy’, Armed Forces & Society 42 (2), 251-75. Bowen, B.E. (2019) ‘From the sea to outer space: The command of space as the foundation of spacepower theory’, Journal of Strategic Studies, 42 (3-4), 532-556.

Brzezinski, Z. (1997) The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives. New York, Basic Books.

Calhoun, M.T. (2011) ‘Clausewitz and Jomini: Contrasting Intellectual Frameworks in Military Theory’, Army History 80 (Summer 2011), 22-37. Chaliand, G., ed. (1994) The Art of War in World History from Antiquity to the Nuclear Age. Berkeley, University of California Press.

Chickering, R. and Förster, S., eds. (2010) War in the Age of Revolution: 1775-1815. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Chlup, J. (2014) ‘Just War in Onasander’s “Strategikos’, Journal of Ancient History 2 (1), 37-63.

von Clausewitz, C. (1976) On War, trs. by P. Paret and M. Howard. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

von Clausewitz, C. (2009) On War, trs. by P. Paret and Michael Howard, B. Heuser ed.. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Colson, B. (2015) Napoleon: On War. Oxford, Oxford University Press. Collins, R. (1998) The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Cambridge, Mass., Belknap Press.

Cooper, B. (2011) ‘Raymond Aron and nuclear war’, Journal of Classical Sociology 11 (2), 203-224.

Cozette, M. (2004) ‘Realistic Realism? American Political Realism, Clausewitz and Raymond Aron on the Problem of Means and Ends in International Politics’, Journal of Strategic Studies 27 (3), 428-453.

Dighton, A. (2018) ‘Jomini v. Clausewitz: Hamely’s Operations of War and Military Thought in the British Army, 1866-1933’, War in History 12 (2018), 1-23.

Drohan, T.A. (2011) ‘Bringing “Nature of War” into Irregular Warfare Strategy: Contemporary Applications of Clausewitz’s Trinity’, Defence Studies 11 (3), 497-516.Earle, E.M., ed. (1941) Makers of Modern Strategy : Military Thought from Machiavelli to Hitler. Princeton, Princeton University Press.Esdaile, C. (2008) ‘De-constructing the French Wars: Napoleon as anti- Strategist’, Journal of Strategic Studies 3 (4), pp. 512-552.Emmanuel, T. (1986) ‘Violence et calcul. Raymond Aron lecteur de Clausewitz’, Revue française de science politique 36 (2), 248-68.Fleming, C.M. (2009) ‘New or Old Wars? Debating a Clausewitzian Future’, Journal of Strategic Studies 32 (2), 213-241.Forrest, A. and Wilson, P.H., eds. (2009) The Bee and the Eagle: Napoleonic France and the End of the Holy Roman Empire, 1806. London, Palgrave Macmillan.Freedman, L. (2013) Strategy – A History. Oxford, Oxford University Press.Freund, J. (1976) ‘Guerre et politique de Karl von Clausewitz à Raymond Aron’, Revue française de sociologie 17 (4), 643-51.Furman Daniel III, J. (2015) ‘Burke and Clausewitz on the Limitation of War’, Journal of International Political Theory 11 (3), 313-330.Gaddis, J. L. (2019) On Grand Strategy. New York, Penguin Books.

Gat, Azar (1989) The Origins of Military Thought from the Enlightenment to Clausewitz. Oxford, Oxford University Press

Gat, Azar (1992) The Development of Military Thought in the Nineteenth Century. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Gray, C. (1999a) ‘Clausewitz Rules, OK? The Future Is the past: With GPS’, Review of International Studies 25, 161-182.

Gray, C. (1999b) Modern Strategy. Oxford, Oxford University Press. Gray, C. (2006) Strategy and History: Essays on theory and practice. London, Routledge.

Griffin, C. (2014) ‘From Limited War to Limited Victory: Clausewitz and Allied Strategy in Afghanistan’, Contemporary Security Policy 35(3), 446- 67.

Hagemann, K. (2015) Revisiting Prussia’s Wars against Napoleon – History, Culture and Autonomy. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Handel, M.I., ed. (1986) Clausewitz and Modern Strategy. London, Frank Cass.

Handel, M.I., ed. (2005) Masters of War: Classical Strategic Thought. London: Routledge.

Harsh, J.L. (1974) ‘Battlesword and Rapier: Clausewitz, Jomini and the American Civil War’, Military Affairs 38 (4), 133-138.

Harste, G. (2011) ‘Fear as a medium of communication in asymmetric forms of warfare’, Distinktion: Scandinavian Journal of Social Theory 12 (2), 193-213.

Hegel, G.W.F. (1956) The Philosophy of History. New York, Dover Publications.

Hench, T.J. (2017) ‘Clausewitz v. Jomini: Putting “Strategy” Into Historical Context’, Academy of Management (online), 30 Nov. 2017, last accessed on 10. February 2020.

Herberg-Rothe, A. (2001) ‘Primacy of “Politics” or “Culture” Over War in a Modern World: Clausewitz Needs a Sophisticated Interpretation’, Defense Analysis 17 (2), 175-186.

Herberg-Rothe, A. (2004) ‘Hannah Arendt und Carl Schmitt Vermittlung von Freund und Feind’, Der Staat 43 (1), 35-56. Herberg-Rothe, A. (2007a) ‘Clausewitz and a New Containment: the Limitation of War and Violence’, in H. Strachan and A. Herberg-Rothe, eds., Clausewitz in the 21st Century. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Herberg-Rothe, A. (2007b) Clausewitz’s Puzzle: The Political Theory of War. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Herberg-Rothe, A. (2008) ‘New Containment Policy: A Grand Strategy for the Twenty-first Century?’, The RUSI Journal 153 (2), 50-54. Herberg-Rothe, A. (2009) ‘Clausewitz’s “Wondrous Trinity” as a Coordinate System of War and Violent Conflict’, International Journal of Conflict and Violence 3 (2), 204-19.

Herberg-Rothe, A. (2014) ‘Clausewitz’s Concept of Strategy – Balancing Purpose, Aims and Means’, Journal of Strategic Studies 37 (6-7), 903- 925.

Herberg-Rothe, A. and Forstle, M. (2016) ‘Clausewitz and the struggle for recognition in a newly globalized world’, International Studies Journal (ISJ) 13 (2) , 7-28.

Herberg-Rothe, A. and Honig, J.W. (2007) ‘War without End(s): The End of Clausewitz?’, Distinktion: Scandinavian Journal of Social Theory 8 (2), 133-150.

Heuser, B. and Hartmann, A.V., eds. (2001) War, Peace and World Orders in European History. London, Routledge.

Heuser, B. (2002) Reading Clausewitz. London, Pimlico.

Heuser, B (2007) ‘Clausewitz’s Ideas of Strategy and Victory’, in H. Strachan and A. Herberg-Rothe, eds., Clausewitz in the 21st Century. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Heuser, B. (2010a) The Strategy Makers. Santa Barbara, CA, Praeger. Heuser, B. (2010b) The Evolution of Strategy. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Heuser, B. (2010c) ‘Small Wars in the Age of Clausewitz: The Watershed Between Partisan War and People’s War’, Journal of Strategic Studies, 33 (1), 139-162.

B. Heuser, (2010d) ‘Guibert – Prophet of Total War?’ in R. Chickering and S. Förster, eds., War in the Age of Revolution: 1775-1815, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2010, pp. 49-68.

Heuser, B. (2013) ‘Victory, Peace, and Justice: The Neglected Trinity’, Joint Forces Quarterly vol. 69 (April 2013), pp. 6-12.

Heuser, B. (2018) Strategy before Clausewitz. Abingdon, Routledge. Heuser, B. (2020) ‘Strategy’s Ethical Imperative from Onasander to Howard via Clausewitz’, Interview by C.A. Olteanu, 27. February 2020. Hoffman, F.G. (2018) ‘Squaring Clausewitz’s Trinity in the Age of Autonomous Weapons’, Foreign Policy Research Institute (Winter 2019), 44-63.

Howard, M. (1965) ‘Jomini and the Classical Tradition’, in M. Howard, ed., The Theory and Practice of War, London, Cassel, pp. 5-20.

M. Howard, ed. (1965) The Theory and Practice of War. London, Cassel.

M. Howard (1967), ‘Strategy and Policy in Twentieth-Century Warfare’, in Texas National Security Review, ‘Roundtable: Remembering Sir Michael Howard (1922-2019)’, 24. Feb. 2020., last accessed on 22. March 2020, at https://tnsr.org/roundtable/roundtable-remembering- sir-michael-howard-1922-2019/

von Hohenzollern, F. II. (1763) Der Siebenjährige Krieg. Ürheberrechsfreie Ausgabe. Kindle (online).

von Hohenzollern, F. II. (1999) Frederick the Great on The Art of War, trs. & ed. by J. Luvaas. New York, DA Capo Press.

Hughes, R.G. and Koutsoukis, A. (2019) ‘Clausewitz first, and last, and always: war, strategy and intelligence in the twenty-first century’, Intelligence and National Security (34) 3, 438-455.

Johnson, R. (2017) ‘The Changing Character of War’, The RUSI Journal 162 (1), 6-12.

de Jomini, A.H. (2007) The Art of War, G.H. Mendell and W.P. Craighill, trns. Rockville, MD, Arc Manor.

Kaempf, S. (2011) ‘Lost through non-translation: bringing Clausewitz’s writings on “new wars” back in’, Small Wars & Insurgencies 22 (4), 548- 573.

Kaldor, M. (2010) ‘Inconclusive Wars: Is Clausewitz Still Relevant in these Global Times?’, Global Policy 1 (3), 271-281.

Kennedy, P., ed. (1991) Grand Strategies in War and Peace. New Haven, Yale University Press.

Kissinger, H. (1973) A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace, 1812-1822. Mariner Books.

Kissinger, H. (1994), Diplomacy. New York, Simon & Schuster.

Kittler, W. (2011) ‘Host Nations: Carl von Clausewitz and the New US Army / Marine Corps Field Manual, FM 3-24, MCWP 3-33.5, Counterinsurgency’, in in E. Krimmer and P.A. Simpson, eds., Enlightened War: German Theories and Cultures of Warfare from Frederick the Great to Clausewitz, Rochester, NY, Camden House, pp. 279-305.

Kunnisch, J. (2005). Friedrich der Grosse: Der König und seine Zeit. München, C.H. Beck.

Lefort, C. (1977) ‘Lectures de la guerre: le ‘Clausewitz’ de Raymond Aron’, Annales. Economies, sociétés, civilizations 32 (6), 1268-79.

Levy, J.S. (2017) ‘Clausewitz and People’s War’, Journal of Strategy. Studies 40 (3), 450-456.

Logothetis, K. (2013) ‘Review: “With a Sword in one Hand and Jomini in the Other: The Problem of Military Thought in the Civil War North”, by C. Reardon’, Civil War History 59 (3), 396-7.

Luttwak, E.N. (2001) Strategy – The Logic of War and Peace’, 3rd ed.. Cambridge, Mass., Belknap Press.

Mackay, D. (2020) How effective approaches to strategy are evolving… and what you should do about it, Lecture delivered at Strathclyde School of Business, Glasgow, Scotland, 30. January 2020.

Mann, T. (1969) The Magic Mountain, New York, Vintage Books.

Mattox, J.M. (2008) ‘The Clausewitzian Trinity in the Information Age: A Just War Approach’, Journal of Military Ethics 7 (3), 202-214.

Milburn, R.M. (2018) ‘On Clausewitz: Reclaiming Clausewitz’s Theory of Victory’, Parameters 48 (3), 55-63.

Mulgan, G. (1998) Connexity: Responsibility, Freedom, Business and Power in the New Century. London, Vintage.

Murphy, M. (2013) ‘Book Review: Strachan, Hew, and Sibylle Scheipers, eds. ‘The Changing Character of War’. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001’, Naval College Review 66 (2), 124-6.

Niebisch, A. (2011) ‘Military Intelligence: On Carl von Clausewitz’s Hermeneutics of Disturbance and Probability’, in E. Krimmer and P.A. Simpson, eds., Enlightened War: German Theories and Cultures of Warfare from Frederick the Great to Clausewitz, Rochester, NY, Camden House, pp. 258-278.

Palaver, W. and Borrud, G. (2017) ‘War and Politics: Clausewitz and Schmitt in the Light of Girard’s Mimetic Theory’, Contagion: Journal of Violence, Mimesis, and Culture 24, 101-117.

Pankakoski, T. (2017) ‘Containment and intensification in political war: Carl Schmitt and the Clausewitzian heritage’, History of European Ideas 43 (6), 649-673.

Paret, P. (1976) Clausewitz and the State. Oxford, Clarendon Press. Paret, P., ed. (1998) Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Parkinson, R. (1970) Clausewitz – A Biography. London, Wayland Publishers.

Rosato, S. (2008) ‘Clausewitz’s Intellectual Journey’, The Review of Politics 70 (3), 510-513.

Schieder, T. (2000) Frederick the Great. London, Longman.

Showalter, D.E. (1996) The Wars of Frederick the Great. London, Longman.

Schuurman, P. (2014) ‘War as a System: A Three-Stage Model for the Development of Clausewitz’s Thinking on Military Conflict and Its Constraints’, Journal of Strategic Studies 37 (6-7), 926-948.

Schweizer, K.W. (2009) ‘Clausewitz Revisited’, The European Legacy 14 (4), 457-461.

Strachan, H. (2005) ‘The lost meaning of strategy’, Survival 47 (3), 33- 54.

Strachan, H. (2007) Carl von Clausewitz’s “On War”: A Biography. London, Atlantic Books.

Strachan, H. (2011) ‘Strategy and Contingency’, International Affairs 87 (6), 1281-96.

Strachan, H. (2013) The Direction of War: Contemporary Strategy in Historical Perspective. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Strachan, H. (2019) ‘Strategy in theory; strategy in practice’, Journal of Strategic Studies 42 (2), 171-190.

Strachan, H. and Herberg-Rothe, A., eds. (2007) Clausewitz in the 21st Century. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Strachan, H. and Scheipers, S., eds. (2011) The Changing Character of War. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Striker, G. (1987) ‘Greek Ethics and Moral Theory’, The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, Stanford, Stanford University, 14-19 May 1987, last accessed on 22. March 2020, at https://tannerlectures.utah.edu/_documents/a-to-z/s/Striker88.pdf. Terhalle, M. (2018) ‘Strategie und Strategielehre’, Z. Aussen Sicherheitspolitik 11 (2018), 83-100.

Vernochet, J.-M. (1987) ‘Raymond Aron. Sur Clausewitz’, Politique étrangère 52 (2), p. 790.

Waldman, T. (2010) ‘Shadows of Uncertainty’: Clausewitz’s Timeless Analysis of Chance in War’, Defence Studies 10(3), 336-368.

Wallach, J.L. (1986) The Dogma of the Battle of Annihilation: The Theories of Clausewitz and Schlieffen and Their Effect on the German Conduct of Two World Wars. Westport, Conn., Greenwood.

Contact us

Become a contributor