FIRST EDITION

VOL THREEJack Mallinson

Following the Principles: Why The Chinese PLAN Should Adhere to Corbett’s Strategy Instead of Mahan’s Precepts

Abstract

Many scholars in the field of Chinese security assert that the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s (PLAN) adheres to the offensive, expansionist naval strategy of Alfred Thayer Mahan. However, by analysing the current strategic and operational capacities of the PLAN, this essay argues that the PLAN ought to adhere instead to the teachings of Mahan’s intellectual opposite, Sir Julian Corbett. By critiquing Corbett’s Principles of Maritime Strategy, this essay will illustrate that Corbettian strategic thought would better serve the PLAN at both the strategic and operational levels. Strategically, adherence to Corbett aligns with the pre-existing ‘Active Defence’ doctrine of the PLAN and would better protect the Maritime Silk Road (MSR) project than would a Mahanist approach. Moreover, at an operational level, the teachings of Corbett align significantly with the PLAN’s A2/AD capacity in the China Sea. Corbettian principles would prove vital in the event of a Taiwan contingency, an avowed goal of the Chinese Communist Party for accomplishment within the next two decades.

Keywords: Corbett, Mahan, Indo-Pacific, Naval Strategy, Active Defence, PLAN, SLOC, A2/AD.

“For China, as for Mahan, control of key points on the map is indispensable to sea power” (Holmes and Yoshihara, 2005: 26). Holmes and Yoshihara are but two academics to note the influence that Alfred Thayer Mahan has had within the PLA Academy of Military Sciences on Chinese naval strategic thought (Ibid). Nevertheless, this essay argues that the PLAN should instead adhere to the tenets of Sir Julian Corbett, in lieu of Mahan’s – and more specifically, to a Corbettian approach at both strategic and operational levels. At the strategic level, the naval strategy theories of the latter align significantly with the well-established, pre-existing PLAN strategy of ‘Active Defence’. Moreover, a more defensive, conservative approach such as that of Corbett’s ‘fleet-in-being’ thesis would better protect and consolidate the Chinese ports and critical sea lines of communication (SLOCs) that are integral to the security of the Belt and Road Initiative’s (BRI) Maritime Silk Road (MSR). This paper posits that due to comparative geographical and quantitative inventory weaknesses to states aligned against the PRC, namely the United States, India, Japan, and ASEAN, adopting the notions of Corbett would produce a more comprehensive defence of the PRC’s strategic aims within the Indo-Pacific. Furthermore, utilising a Mahanian approach exposes the PLAN’s weaknesses, rather than playing to its strengths.

This is compounded by the need for a Corbettian approach at an operational level. In a Taiwan contingency, Corbett’s dictums surrounding ‘Exercising Command’ as a means of integrating naval power with an expeditionary force already corresponds with the PLA’s pre-existing Anti-access area-denial (A2/AD) doctrine. Moreover, this would be in lieu of the need for the PLAN to conduct a ‘decisive battle’ vis-à-vis a potential US-led coalition fleet, as championed by Mahan. Furthermore, the PLAN ought to utilise Corbett’s notion of ‘offence by counterattacks’ in such a scenario, given the comparative strength of Western and Western aligned fleets in the South China Sea, reinforced after the signing of the AUKUS agreement. Thus, due to the vast scope of approaches that Corbett allows in scenarios of strength or weakness, the PLAN would benefit significantly from adopting his strategic thought.

Overview of Theoretical Literature and Mahan’s Role in PLAN Strategic Thought

Sir Julian Corbett (1854-1922) and Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914) are two theorists of great import in the field of naval strategy . In no small measure their importance stems from fundamental divergences between their theoretical tenets. For Mahan, an American naval officer who sought to challenge British naval dominance in the late Nineteenth Century, the primary tenet of naval strategy was ‘the possession of that overbearing power on the sea which drives the enemy’s flag from it’ (Mahan, 1941: 98). Thus, for Mahan, the central aim must be to defeat the enemy in a decisive fleet-on-fleet action (Mahan, 1941: 85). Furthermore, this is compounded by Mahan’s thesis that, even after this ‘decisive action’, one must pursue the remnants of the enemy in an unrelenting attempt to completely annihilate its fleet (Mahan, 1941: 80). It is clear to see, then, why an emerging power like the PRC challenging US dominance in the Indo-Pacific would be influenced by Mahanian rhetoric for total command of the seas. Comparatively, this Clausewitzian ‘total victory’ dictum differs greatly from Corbett’s more attrition-oriented doctrine. For the latter, a British naval historian, the objective of naval warfare was to “directly or indirectly either to secure the command of the sea or to prevent the enemy from securing it” (Corbett, 1911: 87). More specifically, Corbett theorised that command of the sea meant control of communications, which may be partial or total depending on the strength of one’s fleet (Corbett, 1911: 100). Furthermore, Corbett was more detailed vis-à-vis operational methods than Mahan, with the former providing a wider amalgamation of methods than the latter. By dividing naval operations into three core tenets; securing command, disputing command, and exercising command, (Corbett, 1911: 168) Corbett provides an adaptability to naval operations that Mahan in his more singular, ‘decisive action’ approach negates. This is the fundamental factor as to why the PLAN should adopt Corbett’s sophisticated strategic vision in lieu of Mahan’s ‘total victory’ perspective.

Despite this, it is important to note that Mahan’s writings have maintained an important role within PLAN strategic thought, especially throughout the Twentieth Century. During this period PLAN strategists, led by Admiral Liu Huaqing, leaned towards Mahan’s view of absolute control of the sea established by major fleet engagements (Yoshihara and Holmes, 2005: 682). Furthermore, Mahan’s notion for economic expansion via naval power resonated within the PLAN, especially given China’s global economic development, and its increasing reliance on seaborne commerce for oil and liquified natural gas (Holmes and Yoshihara, 2005: 25). It is for this reason that the chief moderniser of the PLAN in the late Twentieth Century, Admiral Liu, drew on Mahan’s axiom for the need for total control of the seas, particularly SLOCs (Lim, 2011: 105-120 and Li, 2009: 155). Thus, one can see that China tied Mahan’s emphasis of ‘decisive action’ and economic development with its own economic expansion, especially beyond the confines of East and Southeast Asia. Nevertheless, the more defence-oriented, conservative approach proclaimed by Corbett better protects and unifies the PRC’s security interests throughout the Indo-Pacific, as opposed to the Mahanian thought of driving ‘the enemy out of every foothold in the whole theatre’ (Mahan, 1941: 85).

Strategic Level: Corbett Within the ‘Active Defence’ and Maritime Silk Road Frameworks

Active Defence

One of the most significant factors that the current PLAN must utilise is the PLA’s pre-existing Active Defence strategy. The PLA defines Active Defence as an “adherence to the unity of strategic defence and operational and tactical offence; adherence to the principles of defence” (State Council Information Office of the PRC, 2015). For the PLAN specifically, this revolves around a symbiotic relationship between “offshore waters defence” with “open seas protection” (State Council Information Office of the PRC, 2015).

Two things are of critical importance for the purposes of this essay. Firstly, Active Defence is inherently a defensive – not offensive – strategy. This is vividly illustrated by the PLA’s published strategy in 2015 stating that the PLAN will primarily focus not only on comprehensive support, but on both deterrence and counterattacks (State Council Information Office of the PRC, 2015). Moreover, this document illustrates that a defensive strategy is adopted by China for offensive ends. President Xi Jinping’s ‘China Dream’ – the national rejuvenation and restoration of PRC global power – places the PLAN in direct support of the PRC’s expansionist foreign policy (Fanell, 2019: 14). It is due to this that, over seven years after the reiteration of the centrality of Active Defence and the core role of the PLAN within this framework, the US Department of Defence (DoD) stated in 2021 its view that the maintenance of Active Defence remains the PRC’s military strategy (US DoD, 2021: v). Thus, it is evident that Active Defence is a core facet of the PLAN’s overall strategy.

Not only is Active Defence one of the single most important considerations for the PLAN, but it is also Corbettian, and should be conducted in-line with Corbett’s strategic thought. The defensive nature of the PLAN’s primary role, the deterrence of foreign states from Chinese interests (Martinson, 2021: 265), in the form of Active Defence is inherently defensive and thus aligns with a Corbettian approach. Corbett’s axiom of securing command by obtaining a decision through ‘offensive defence’ i.e., waiting deliberately to implement counterattacks (Corbett, 1911: 33) aligns significantly with the core Active Defence tenet of defence through deterrence and counterattacks (State Council Information Office of the PRC, 2015). Therefore, this clearly correlates more with Corbett’s notion of negating the ‘seeking out’ a decisive decision (Corbett, 1911: 176). Moreover, the ‘far-seas protection’ tenet of Active Defence relies on a reactive posture to protect SLOCs rather than securing demand through decisive fleet engagements (Fravel, 2019: 232). Thus, it is clear that Active Defence not only aligns with Corbett’s notion regarding the securing of command through counter offensives to obtain a decision, but actively goes against the Mahanian approach of singular, purely offensive fleet engagements (Mahan, 1941: 98). It is this, and the centrality of Active Defence in the PLAN’s strategy, that should cause the PRC to gravitate towards Corbett’s strategic thought instead of a Mahanian approach.

Maritime Silk Road (MSR)

The MSR is of critical importance to the PRC not only now, but throughout the foreseeable future. As a means of diversifying Chinese trade across land and sea, the MSR forms part of the BRI by placing seaports strategically throughout 2122 km of the Indo-Pacific (Singh and Pradhan, 2019: 22). These ports allow for greater connection between China and its chief oil supplier, the Middle East, by allowing the PLAN to better protect the SLOCs (Ji, 2016: 12). Chinese-lease ports, such as Gwadar in Pakistan near the Strait of Hormuz, and others in Cambodia and Myanmar will provide strategic locations for the PLAN to help the MSR overcome the ‘Malacca Dilemma’- the primary goal of the MSR (Mobley, 2019: 55). The significance of this cannot be overstated. In 2019, 89 percent of Chinese crude oil imports came via maritime shipping, with 75 percent of this trade passing through the Strait of Malacca (Wang and Su, 2021: 1). Thus, the ‘string of pearls’ ports from Djibouti, Pakistan, Hanbantota Sri Lanka, Chittagong in Bangladesh, through to Cambodia and Myanmar allow for enhanced maritime security along the PRC’s core trade routes (Lin, 2008: 1). In doing so, the PLAN has firmly established a symbiotic relationship between the PLAN and MSR.

Adopting Corbett’s approach within the Active Defence framework would undoubtedly best protect the PRC’s SLOC security in the vicinity of these ports. SLOC protection requires the ability to sustain a prolonged maritime presence in strategic locations under hostile conditions (ONI, 2015: 11). The PLAN can achieve this by utilising two core factors. Firstly, the maintenance of ports such as Gwadar (Pakistan) and Doraleh (Djibouti) increases the PLAN’s ability to exercise control of crucial SLOCs (DIA, 2019: 29). In doing so, the ports allow the PLAN to adhere to Corbett’s notion of obtaining a decision via major counterattacks or blockade (Corbett, 1911: 168). Significantly, this can be achieved within the PLAN’s Active Defence framework; Corbettian counterattacks through the prism of Active Defence can be done so due a utilisation of these ports. Not only will the PLAN’s increased blue-water capabilities allow for this (DIA, 2019: 36), but the symbiotic relationship between Corbett’s strategy and Active Defence would be the means by which SLOC protection could be best conducted. Moreover, this would further tie-in with the PLAN’s primary aim in ‘open-seas protection’ to protect the PRC’s strategic maritime interests, such as the Straits of Malacca and Hormuz (ONI, 2015: 11). Thus, defensive aims require defensive means, which is the fundamental rationale for the PLAN adopting Corbett’s dictum of obtaining a decision via counterattacks or by a blockade .

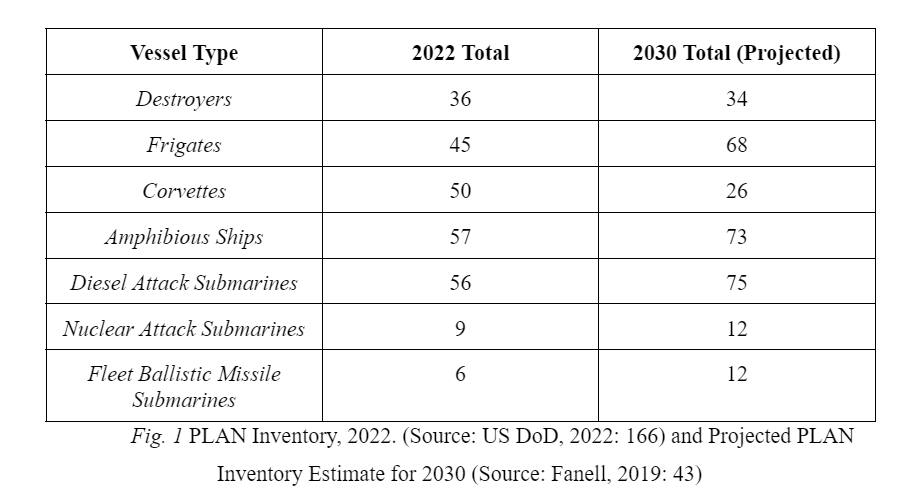

A critical factor explaining why the PLAN significantly enhances its credibility by adopting a Corbettian ‘fleet-in-being’ in order to protect SLOCs and MSR ports is the size of its fleet as compared with Western or de facto Western navies. Fig.1 illustrates that the PLAN has expanded significantly into one of the largest naval fleets globally (Fanell, 2019: 43). Despite this projected inventory growth, the PLAN will comparatively be no greater in size than a potential coalition led by the US Navy’s 7th and 5th Fleets (Paszek, 2021: 177).

Furthermore, Chinese expansion in the region has solidified security partnerships between the US and its allies, with the Biden administration committing itself to a ‘free and open’ Indo-Pacific with Japan (White House, 2021). Compounding this issue is India’s ‘Act East’ policy, which has seen a dramatic increase in its naval inventory and has pushed India into closer cooperation with the US in SLOC security in the Straits of Malacca and Singapore (Collin, 2019: 7-8). More recently, the signing of the AUKUS nuclear-powered attack submarine (SSN) deal that will result in Australia acquiring potentially five Virginia class SSNs, multiple Anglo-Australian SSNs and the increased presence of US and British SSNs in the Indo-Pacific are also directly aimed against the PLAN (AUKUS, 2023: 4-8). Thus, China will have to challenge a de facto US-led naval coalition for control of SLOCs.

Ultimately, these factors weigh in favour of adopting Corbett’s ‘fleet-in-being’ dictum in lieu of Mahan’s ‘decisive action’ precept. The PLAN, in 2020, outnumbered the US Navy by 360 battle force ships to 297 (Sweeney, 2020: 2). This, however, fails to consider the amalgamation of security agreements and pacts in the region. The US and Japan recommitted closer ties to Quad nations, including Australia and, significantly, India, in 2021 (White House, 2021). The AUKUS agreement compounds this further by creating a new SSN fleet in the Indo-Pacific, the Royal Australian Navy, and committing Anglo-American security priorities to the region throughout the next several decades (AUKUS, 2023: 4). Here again, a Corbettian approach better serves the PLAN’s SLOC protection ability. Corbett’s dictum of keeping the “fleet in being till the situation develops in our favour” (Corbett, 1911: 213) would be a highly suitable means to adhere to Active Defence’s protection of SLOCs against what would be a greater naval coalition by size. Moreover, this, and the mere presence of PLAN combatants around PRC leased ports, also allows for counterattacks in a favourable situation. This can only be achieved by actively keeping the fleet in being (Corbett, 1911: 214). Compounding this further is that, given the comparative PLAN fleet size vis-à-vis the amalgamation of US-aligned fleets, the PLAN would be unlikely to successfully conduct a Mahanian ‘decisive action’, fleet-on-fleet battle.

Furthermore, a Corbettian approach also better consolidates and protects other, land-based aspects of the BRI than a Mahanist approach would, compounded by the issues of the MSR and comparative fleet inventories. The China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) utilises the Gwadar-Kashgar gas pipeline to connect Yunnan Province with the Bay of Bengal (Mobley, 2019: 63). In doing so, CPEC allows the PRC to better contend with US-Indian security cooperation efforts in the region, meaning better protection of vital SLOCs (Lloyd, Gul and Ahmed, 2021: 3). This project is not only a means to diversify energy imports, but also helps mitigate the fact that the PLAN does not, and will not in the foreseeable future, be capable of upending US naval supremacy in the Indo-Pacific (Gordon, Tong, and Anderson, 2020: 14). The project integrates military support from ports such as Gwadar and Hanbantota into the PRC’s wider economic strategy (Wang and Su, 2021: 2). Due to this, adopting Corbett’s tenet of defence via counterattacks would best protect these land-based aspects of the BRI. Moreover, this is even more the case given the significant degree of alignment between Corbettian strategy and Active Defence, which in itself is a means to protect the PRC’s global economic projects, primarily the BRI (State Council Information Office of the PRC, 2015).

Compounding this further is the comparative inventory issue that the PLAN has between the naval fleets Quad, AUKUS, and ASEAN states. This issue does not only make adopting a more defensive strategic thought such as Corbett’s desirable, but means that a more aggressive strategy, such as Mahan’s, may be a highly unsuccessful venture for the PLAN. Thus, wider BRI factors also illustrate why the PRC ought to adhere to Corbett’s strategy of obtaining a decision in a more conservative manner via counterattacks instead of Mahan’s more assertive precepts.

Operational Level and Taiwan Contingency

At a lower, operational level, Corbett’s strategic thought correlates significantly with the PLAN’s pre-existing dictum of anti-access area-denial (A2/AD). Importantly, the PLAN’s A2/AD capacity is directed at the island of Taiwan itself, given that Taiwan remains the PRC’s primary operational target (Wuthnow and Fravel, 2022: 7). As an operational means of conducting the ‘offshore defence’ tenet of Active Defence, A2/AD is the PLAN’s primary means of deterring the US Navy away from any cross-Strait contingency vis-à-vis Taiwan (Morton, 2016: 933). This is a maintained operational dictum within the PLAN as it is the only means by which the PLAN can secure the area within the first island chain due to the superiority of the US Navy (Horta, 2012: 395). Due to A2/AD inherently being a defensive mode of operations against an opponent of potentially greater military power (Tangredi, 2019: 8) this correlates strongly with Corbett. Foremost, it adheres to Corbett’s notion that if a navy is not sufficiently strong to have total control of SLOCs, then a more localised degree of control denies the enemy total dominance (Corbett, 1911: 100). Not only that, but A2/AD inherently incorporates Corbett’s use of blockades (anti-access) and counterattacks (area-denial) as methods of securing command (Corbett, 1911: 168). The fact that A2/AD is a core tenet of the PLAN’s established ‘offshore defence’ doctrine, which in itself is a facet of Active Defence, means that the overall PLAN strategy inherently adheres to Corbett’s methods of securing maritime command.

The substantial number of submarines that the PLAN boasts in its inventory would be best utilised by adhering to Corbett over Mahan within this pre-existing A2/AD framework. In particular, the build-up of diesel-electric submarines has been done so as to better conduct anti-access operations around Taiwan in the East China Sea (Lim, 2017: 156) By conducting a blockade of Taiwan within this A2/AD framework, the diesel-electric submarine fleet would play an integral role in laying mines at Taiwanese ports (Wuthnow, 2020: 17). Moreover, the fact that the PLAN submarine fleet is equipped with anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs) in order to conduct anti-surface warfare (ASUW) demonstrates that this fleet is designed for A2/AD operations (ONI, 2015: 19). Due to this, adopting Corbett’s dictums in lieu of Mahan’s precepts would better utilise the strengths of the pre-existing PLAN submarine fleet. The mode of operations the PLAN are geared towards aligns with two Corbettian notions: firstly, that in a blockade, one denies the enemy access to lines of communication, as a means of denying opposing forces control of this passage; (Corbett, 1911: 89) and as a method of exercising command via counterattacks (Corbett, 1911: 29). Conversely, an approach that adheres to Mahan’s dictums would demand that this submarine fleet, that is inherently geared towards defensive operations, be used in highly offensive, decisive fleet battles that contradicts how these vessels already operate within an A2/AD framework. Thus, the PLAN ought to adhere to Corbett’s inherent conservatism in naval operations planning to better utilise the pre-existing orientation of its submarine fleet within an A2/AD context.

Furthermore, adopting Corbett’s precepts at an operational level also better integrates the PLA’s Rocket Force (PLARF) within this A2/AD framework. The PLARF is a key platform that allows the PLA to develop the capacity to defy and deter a US-led coalition in a Taiwan contingency situation (Gill and Ni, 2019: 174). The placement of anti-ship ballistic-missiles (ASBMs) such as the Dongfeng-21D adjacent to Taiwan allows the PRC to enhance its A2/AD capabilities to the extent that the PLA has the ability to deter a US aircraft carrier group away from the Taiwan vicinity (Yevtodyeva, 2022: 536). Thus, for this facet of area-denial within A2/AD to be effective, coordination and integration between the PLAN and PLARF is required (Cunningham, 2020: 763). Adhering to Corbett’s strategic thought would allow for this integration. Foremost, in support of military operations, Corbett argues that naval forces are a means to their own ends – they should be part of a ‘combined expedition’ (Corbett, 1911: 289).

Moreover, Corbett himself argues that when the theatre of combat is within a defended area, a port defence squadron is able to sufficiently defend operations, rather than giving the expedition its own covering squadron (Corbett, 1911: 293). Importantly, adopting this operational theory would allow PLAN combatants, that are already geared towards A2/AD operations, to not overstretch their concentration of force by allowing the PLARF to play a critical role in area-denial, thus better protecting the PLA’s amphibious assault on Taiwan proper. An adherence to Corbett’s notions on the integration of naval fleets with military expeditions by the PRC within the mode of A2/AD would therefore allow for a more cohesive combined assault vis-à-vis Taiwan.

The pre-existing operational structure of the PLAN makes a Mahanian approach significantly ill-suited, further compounding the degree of credibility of the Corbettian approach. Given that the reclamation of Taiwan remains a core focus of the PRC’s ‘New Era’ (DoD, 2021: v), and that an integrated, combined expeditionary force would be required, Mahanian thought does not allow for such an operational dictum. For Mahan, one ought to acquire total control of SLOCs, such as the Taiwan Strait, through unrelenting fleet-on-fleet action (Mahan, 1941: 98). The primary aim, therefore, must be destruction of the enemy fleet (Mahan, 1941: 85). Within the context of a Taiwan contingency, this does not suit the PLAN due to two crucial factors; comparative fleet size, and the pre-existing focus of the PLAN’s operational focus in the region being defensive not offensive. Regarding the former, it is highly unlikely that the PLAN would be able to comprehensively defeat the United States Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM), consisting of 2000 aircraft and 200 ships and submarines (DoD, 2019: 19). Such an overtly aggressive approach would be rendered even more unwise, given that this USINDOPACOM force would be supported by an amalgamation of allies in the region, namely Japan, India, and ASEAN countries (DoD, 2022: 14-15). Seeking decisive action against such a coalition would most likely be highly risky. Moreover, Mahan’s precepts do not align well with the PRC’s A2/AD operational dictum, which is its primary operational thought for a war with Taiwan so as to deter other belligerents (Wuthnow, 2020: 17). Thus, the stark differences between Mahan’s strategy and the PLAN capacity vis-à-vis Taiwan lends further credence to Corbett’s dictums operationally.

In fact, if the PRC were to adopt Corbettian thought at an operational level, it would also better consolidate and protect important Chinese sovereignty interests in the South China Sea. The PRC uses maritime law enforcement vessels to expand its control of disputed features, namely the Spratly Islands (DIA, 2019: 28). This is a means to significantly increase the overall strength of the PRC’s A2/AD capabilities, by expanding the scope of the ‘offshore waters defence’ facet of the PLAN’s anti-access tenet due to an expanded ability to deter by military force and sustain foreign operations (DIA, 2019: 29). This is the operational method most suited to expand Chinese influence by pushing “ASEAN claimants to recognise Chinese sovereignty” (Buszynski, 2012: 19). Adhering to Corbett’s notion that “command of the sea, therefore, means nothing but the control of maritime communications” (Corbett, 1911: 90) would allow the PRC to successfully consolidate its territorial claims within the region. Crucially, because this expansion is a facet of the PRC’s ‘offshore waters defence’, it inherently aligns with Corbettian thought regarding the protection of SLOCs and dispute of maritime command via providing the PLAN with the ability to conduct counterattacks and blockades in adherence to its A2/AD doctrine.

Proponents of a Combined ‘Anti-Mahan, Pro-Corbett’ Approach

There are some that are proponents of merging specific concepts that Mahan criticised with a purely Corbettian concept. Ultimately, the PRC would be better advised to focus on Corbett’s operational thought than on Mahan’s dislike of a ‘fortress fleet’. Holmes, the sole academic to advocate such an approach, puts forth the notion that the PLAN ought to utilise what Mahan called a fortress fleet, one that operates under the cover of shore-based fire (Holmes, 2010: 115). From this perspective, not only would this strategy allow for the PLAN to operate safely in a Taiwan contingency, but it should be fully integrated with Corbett’s dictum of a fleet-in-being in the region (Holmes, 2010: 124). Any validity to this notion resides in the fact that it connotes the need for PLAN to maintain a defensive operational posture, especially around the East and South China Seas.

Nevertheless, Holmes fails to exploit the full potential of Corbett’s strategy for the PLAN. Holmes spends too much time critiquing Mahan’s disregard for fortress fleets, when a better approach would have been to advise the PLAN to adhere to Corbett’s notion of concentrating naval combatants around protection of the expeditionary fleet within a defended area, away from terminal protection as to utilise a better concentration of forces (Corbett, 1911: 293). Whilst this does inherently align with fortress fleets in theory, pragmatically Corbett’s dictum provides greater operational flexibility, given that a ‘defended area’ does not necessarily have to be one provided by land-based firepower as with a fortress fleet. Thus, whilst there is a degree of validity to Holmes’ argument, the PLAN ought to adopt a more purely Corbettian approach for enhanced operational flexibility.

Conclusion

This paper makes a strong argument in favour of the PRC’s need to adopt the strategic and operational thought of Corbett for the PLAN over Mahan’s precepts of naval warfare. Corbett’s strategic thought aligns significantly not only with the PLAN’s pre-existing strategic and operational dictums but also with likely future strengths and constraints at these levels of warfare. Strategically, it is highly compatible with the PLAN’s Active Defence strategy, given that this emphasises defence rather than offence. Corbett’s notions regarding the use of counterattacks via a fleet-in-being would provide the PLAN with greater SLOC protection by utilising the ‘string of pearls’ across the MSR. Thus, adhering to Corbettian principles within the Active Defence framework would protect and maintain the PRC’s MSR, compounded by the fact that adopting a Mahanian approach would be counter-productive, given that the PRC is, and will likely continue to, compete with a de facto US-led coalition throughout the Indo-Pacific. At a more operational level, Corbettian thought allows the PLAN to be more effective in the PRC’s chief operational aims: a Taiwan contingency and increasing expansion in the South China Sea. Corbett’s notions regarding his fleet-in-being dictum and the exercise of command again align significantly with the PLAN’s A2/AD dictum.

Nevertheless, it ought to be noted that more research within this particular area of contemporary naval strategy is required. For instance, further research is required on the extent to which a Corbettian approach to PLAN strategy conforms with the political aspect of any future attempts by the PRC to reintegrate Taiwan with the mainland. This is of real import, as any lack of alignment of Corbett’s strategic thought with the political facet of Taiwanese integration with the mainland PRC would undermine the extent to which Corbett’s dictum enhances the operational level of a potential Taiwan contingency.

Furthermore, it is of equal importance to undertake future research on a US or Western policy maker’s perspective, specifically, an analysis of whether US deployments to the Indo-Pacific would, theoretically, be suitable against the PLAN adhering to Corbett’s. Incorporating the AUKUS Agreement into such a response would be of equal importance: achieving credible deterrence without exacerbating geopolitical tensions to a point where they snap. Given the significance of this topic, future research on how deterrence is achievable without increasing geopolitical tensions with the PRC is particularly advisable.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Buszynski, L. (2012) ‘Chinese Naval Strategy, the United States, ASEAN and the South China Sea’. Security Challenges, 8(2), 19-32, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26468950. [Accessed 7th March 2023]

Corbett, J. (1911) Principles of Maritime Strategy. London, Longmans.

Collin, K.S.L. (2019) ‘China-India rivalry at sea: capability, trends and challenges’. Asian Security, 15(1), 5-24, https://doi.org/10.1080/14799855.2019.1539820. [Accessed 9th March 2023]

Cunningham, F.S. (2020) ‘The maritime rung on the escalation ladder: naval blockades in a US-China conflict’. Security Studies, 29(4), 730-768, https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2020.1811462. [Accessed 13th March 2023]

Defence Intelligence Agency. (2019) ‘China Military Power, Modernising A Force To Fight and Win’. Defence Intelligence Agency, Washington DC. Available at: AD1066163.pdf (dtic.mil) [Accessed 8th March 2023]

Fanell, J.E. (2019) ‘China’s global naval strategy and expanding force structure’. Naval War College Review, 72(1), 10-55. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26607110. [Accessed 8th March 2023]

Fravel, M. T. (2019) Active Defence: China’s Military Strategy Since 1949. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gill, B. and Ni, A. (2019) ‘The People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force: reshaping China’s approach to strategic deterrence’. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 73(2), 160-180, https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2018.1545831. [Accessed 9th March 2023]

Gordon, D.F., Tong, H. and Anderson, T. (2020) ‘Beyond the Myths–Towards a Realistic Assessment of China’s Belt and Road Initiative: The Security Dimension’. International Institute for Strategic Studies. Available at: https://ispmyanmarchinadesk.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/BRI-Report-Two-Beyond-the-Myths-Towards-a-Realistic-Assessment-of-Chinas-Belt-and-Road-Initiative.pdf. [Accessed 8th March 2023]

United Kingdom Ministry of Defence. (14th March 2023) The AUKUS Nuclear Powered Submarine Pathway: A Partnership For The Future. HM Government. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1142588/The_AUKUS_nuclear_powered_submarine_pathway_a_partnership_for_the_future.pdf [Accessed 10th March 2023]

Holmes, J.R. (2010) ‘A Fortress Fleet for China’. Whitehead J. Dipl. & Int’l Rel., 11, 115, https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/whith11&div=28&id=&page=. [Accessed 11th March 2023]

Holmes, J.R. and Yoshihara, T. (2005) ‘The influence of Mahan upon China’s maritime strategy’. Comparative Strategy, 24(1), 23-51, https://doi.org/10.1080/01495930590929663. [Accessed 7th March 2023]

Horta, L. (2012) ‘China Turns to the Sea: Changes in the People’s Liberation Army Navy Doctrine and Force Structure’. Comparative Strategy, 31(5), 393-402, https://doi.org/10.1080/01495933.2012.711117. [Accessed 7th March 2023]

Ji, Y. (2016) ‘China’s emerging Indo-Pacific naval strategy’. Asia Policy, (22), 11-19, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24905134. [Accessed 8th March 2023]

Li, N. (2009) ‘The evolution of China’s naval strategy and capabilities: from “near coast” and “near seas” to “far seas”’. Asian Security, 5(2), 144-169, https://doi.org/10.1080/14799850902886567. [Accessed 8th March 2023]

Lim, Y.H. (2017) ‘Expanding the dragon’s reach: The rise of China’s anti-access naval doctrine and forces’. Journal of Strategic Studies, 40(1-2), 146-168, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2016.1176563. [Accessed 14th March 2023]

Lin, C.Y. (2008) ‘Militarisation of China’s Energy Security Policy–Defence Cooperation and WMD Proliferation Along its String of Pearls in the Indian Ocean’. Institut für Strategie- Politik- Sicherheits- und Wirtschaftsberatung. Available at: https://ketlib.lib.unipi.gr/xmlui/handle/ket/478. [Accessed 15th March 2023]

Lloyd, W.F., Gul, A. and Ahmad, R. (2021) ‘Contemporary Assessment of the United States and China Naval Vision for the Indian Ocean Region (IOR)’. Journal of Public Affairs, 21(2), 1-6, https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2573. [Accessed 10th March 2023]

Mahan, Alfred Thayer. (1941) Mahan on Naval Warfare, edited by A. Westcott. New York: Dover Publications.

Martinson, R.D. (2021) ‘Counter-intervention in Chinese naval strategy’. Journal of Strategic Studies, 44(2), 265-287, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2020.1740092. [Accessed 12th March 2023]

Mobley, T. (2019) ‘The belt and road initiative’. Strategic Studies Quarterly, 13(3), 52-72, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26760128. [Accessed 11th March 2023]

Morton, K. (2016) ‘China’s ambition in the South China Sea: is a legitimate maritime order possible?’. International Affairs, 92(4), 909-940, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12658. [Accessed 12th March 2023]

Paszak, P. (2021) ‘The Malacca strait, the south China sea and the Sino-American competition in the Indo-Pacific’. Journal of Asian Security and International Affairs, 8(2), 174-194., https://doi.org/10.1177/23477970211017494. [Accessed 11th March 2023]

Sweeney, M. (2020) ‘Assessing Chinese Maritime Power’. Defense Priorities, Available at: ,https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/assessing-chinese-maritime-power. [Accessed 14th March 2023]

Singh, H. and Pradhan, R.P. (2019) ‘Taiwan, Hong Kong & Macau in China’s infrastructure-diplomacy and the China Dream: Will the dominions fall?’. Maritime Affairs: Journal of the National Maritime Foundation of India, 15(1), 15-26, https://doi.org/10.1080/09733159.2019.1637428. [Accessed 9th March 2023]

State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China. (2015) China’s Military Strategy, Defence White Paper. [Accessed 4th March 2023], https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2015/05/27/content_281475115610833.htm

Tangredi, S.J. (2019) ‘Anti-Access Strategies in the Pacific: The United States and China’. The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters, 49(1), 3, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2859&context=parameters. [Accessed 11th March 2023]

United Kingdom Ministry of Defence. (14th March 2023) The AUKUS Nuclear Powered Submarine Pathway: A Partnership For The Future. HM Government. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1142588/The_AUKUS_nuclear_powered_submarine_pathway_a_partnership_for_the_future.pdf [Accessed 10th March 2023]

United States Department of Defence. (2022) ‘2022 Report on Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China’. Department of Defence, Washington DC. Available at: 2022 China Military Power Report (CMPR) (defense.gov) [Accessed 20th June 2023]

United States Department of Defence. (2021) ‘Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China’. Department of Defence, Washington DC. Available at: 2021 CMPR FINAL (defense.gov) [Accessed 5th March 2023]

United States Department of Defence (2019) ‘The Department of Defence Indo-Pacific Strategy Report: Preparedness, Partnerships, and Promoting A Networked Region’. Department of Defence, Washington DC. Available at: DEPARTMENT-OF-DEFENSE-INDO-PACIFIC-STRATEGY-REPORT-2019.PDF [Accessed 5th March 2023]

United States Department of Defence. (2022) ‘2022 National Defence Strategy of the United States of America’. Washington DC: Department of Defence. Available at: 2022 National Defense Strategy, Nuclear Posture Review, and Missile Defense Review. [Accessed 7th March 2023]

United States Office Of Naval Intelligence, I. B. (2015) The PLA Navy: new capabilities and missions for the 21st century. Office of Naval Intelligence. Available at: https://lccn.loc.gov/2014496604. [Accessed 13th March 2023]

Wang, K.H. and Su, C.W. (2021) ‘Does high crude oil dependence influence Chinese military expenditure decision-making?’, Energy Strategy Reviews, 35, p.100653, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2021.100653. [Accessed 13th March 2023]

White House, (April 16th 2021) ‘US-Japan Joint Leaders Statement, US-Japan Global Partnership for a New Era’. [Accessed 15th March 2023], U.S.- Japan Joint Leaders’ Statement: “U.S. – JAPAN GLOBAL PARTNERSHIP FOR A NEW ERA” | The White House

Wuthnow, Joel. (2020) ‘System Overload: Can China’s Military Be Distracted In A War Over Taiwan?’, Washington DC: National Defence University Press.

Wuthnow, J. and Fravel, M.T. (2022) ‘China’s military strategy for a ‘new era’: Some change, more continuity, and tantalising hints’, Journal of Strategic Studies, 1-36, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2022.2043850. [Accessed 11th March 2023]

Yevtodyeva, M.G. (2022) ‘Development of the Chinese A2/AD System in the Context of US–China Relations’, Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 92 (6), 534-542, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1134/S1019331622120048. [Accessed 15th March 2023]

Contact us

Become a contributor