SECOND EDITION

Timon Ostermeier

Why Russia and the West Did Not Develop Joint Security Structures

ABSTRACT

At the end of the Cold War, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev promoted the idea of a ‘Common European Home’, and after President Boris Yeltsin took office, following the implosion of the Soviet Union, it seemed like Russia was heading for a Western foreign policy direction. However, relations with Western institutions and countries crumbled gradually and turned hostile, hitting rock bottom with the Russian annexation of the Crimean peninsula in 2014. This essay analyzes why no joint security structure between the West and Russia emerged, though post-Cold War initiatives had been brought forward in the international arena. Four factors are pivotal: 1) the failure in progressing the CSCE/OSCE process, 2) Russia’s struggle with its identity as a fallen superpower, 3) the continuity of Cold War mindsets in elite groups, and 4) Russia’s opposition towards NATO’s gradual Eastern expansion. Concluding the analysis, four causal links and a juxtaposition of the competing Transatlantic and Russian security concepts will be derived.

Key Words: Russia; NATO; OSCE; Common European Home; Transatlantic Security; Russian Security; Security Dilemma; Putin

Introduction

Until 30 years ago, the NATO alliance and the Russian-led Warsaw Treaty bloc defined the international order. The unexpected implosion of the Soviet Union, however, gave a blow to the Warsaw Treaty and thereby to global bipolarity. Initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev’s reform policy and ‘New Thinking’, this process was accompanied by a new rapprochement between East and West. Therefore, the dissolution of the communist bloc raised the question of how to transform the former rivalry into a new international order.

Correspondingly, the last leader of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, formulated the pan-European idea of a ‘Common European Home’. The American scientist Francis Fukuyama, meanwhile, invented the notion of the “End of History” – predicting the global implementation of the Western liberal democracy model (Fukuyama, 1989: 4; Fukuyama 1992). Both remained wishful thinking. Today, there is no Common European Home, and instead of liberal democracy, Russia has been described as a “competitive authoritarian” system, being more authoritarian than democratic (Levitsky and Way, 2010: 3; 2002: 51). Quite contrary to the high expectations, a new confrontation between Russia and the West manifested itself: Russia and the European Union eventually competed over the regional integration of Ukraine, which tore the country apart. The Russian Federation annexed the Crimean peninsula, and NATO bolstered military presence on its Eastern flank, close to its borders with Russia. Beyond Europe, Russia returned as a decisive veto player in the Middle East, especially in the Syrian war.

This essay aims to account for the failure to include Russia in joint security structures in the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s collapse. In the following sections, four major factors which inhibited a successful integration will be illustrated: the missed opportunity of establishing a new pan-European security structure within the CSCE/OSCE framework; Russia’s struggle with its identity as a fallen (and possibly future) superpower; the continuity in hawkish leaders and cold war mindsets in both Russia and the West; and – as the most crucial point to the argument – the overarching security dilemma of NATO’s Eastern expansion and Russia’s inability to ally with Central and Eastern European states.

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE):

Too many tasks at once

Why did the Russian Federation and the West fail to construct a joint security structure, a ‘Common European Home’? One crucial point of this issue is the question whether there had been the will to do so: what were the intentions and perspectives in the East and the West? As it will be discussed later, NATO remained the pivotal institution, bolstered by subsequent expansions into the former adversary communist bloc. Accordingly, it was mostly Russia who tried to give incentives for an alternative security architecture with the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE), later renamed into Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) (Smith, 2018).

Apart from the continuity of Cold War mindsets among decision-makers, Horst Teltschik, former chief advisor to German chancellor Helmut Kohl, explained the failure of the CSCE-process by highlighting structural factors: too many challenges overwhelmed the actors at an accelerating pace. Germany was occupied with socio-economic incorporation of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR), and the European Union gained new momentum in its integration process (including the formulation of a common foreign and security policy); NATO remained in place as the main Western security structure; the liberalization of global trade progressed with the creation of the World Trade Organization in 1995; the First Gulf War and the Yugoslav Wars overshadowed all events (Teltschik, 2019: 58–68). On the Russian side, Moscow struggled internally with the disintegration of the former Soviet empire: ethnic conflicts (foremost in the North Caucasus), an economic reform process culminating in economic and financial crisis, a democratization process disrupted by the coup against Soviet leader Gorbachev, and two years later the illegal dissolution and shelling of the parliament by the Russian president Boris Yeltsin.

However, the Charter of Paris For a New Europe (1990) carried the idea of a joint security architecture stretching from Vancouver to Vladivostok; Gorbachev expected it to be a blueprint for the ‘Common European Home’ (CSCE, 1990; Teltschik, 2019: 58–62). The subsequent CSCE conventions encompassed political, military, economic, and environmental dimensions, including conflict prevention mechanisms and – with increasing emphasis – human rights monitoring. However, the multitude of topics put on the agenda and the large number of involved member states overstretched institutional capacities. In the end, the OSCE lacked prioritization and selective pragmatism in accommodating the West and Central-Eastern European integration processes alongside the concurrent disintegration of the former Soviet Union (Teltschik, 2019: 79–84).

Additionally, the humanitarian dimension of the OSCE led to conflicts with Russia about its domestic development (the case of Chechnya, elections, and human rights violations). Thus, Russia found itself in an organization in which it could not actively implement its objectives – instead, Moscow became a rather passive recipient of criticism. Consequently, Russia’s cooperativeness declined, and Moscow even limited the access for OSCE election monitoring (Smith, 2018: 382–85). Still, the annual Foreign Ministers’ meetings mostly take place, but the summits of the heads of state were suspended between 1999 and 2010. The reactivation of the OSCE process passed fruitlessly.

Russia’s identity as a fallen superpower under American primacy

Nalbandov (2016: 24) defines four pillars of Russian political culture: identity, the notion of power, views on authority, and the historical role of territory in the nation-building process. Before turning to the pivotal role of NATO, it therefore seems imperative to stress the role of Russia’s geopolitical identity. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia obviously lost the ideological rivalry with the capitalist West. Moscow even lost territories which had been conquered by the Tsarist empire. In economic terms, Russia hit rock bottom in an utmost humiliating manner, as it found itself requesting financial aid and food assistance from America and Western European countries (Reuters, 1991; Kramer, 1999). Consequently, every second Russian indicated feeling ashamed of this decay, and around 75% demanded that Russia maintain its role as a superpower (Levada Center, 2019). Despite being close to a developing country, Russia preserved distinctive superpower features: its geographic vastness as the largest country in the world, its status as a nuclear power, and as a permanent member with a veto right in the UN Security Council. Alongside these structural preconditions, Russia’s richness in natural resources suggested its potential to compensate for technological and economic backwardness, to some degree. On these grounds, Russia represented a ‘halted’ superpower, too big to be treated as a junior partner – what it actually was at the very moment. (For a discussion on why Russia was not a superpower, see MacFarlane, 2001.) As suggested by Tsygankov (2012), honor and its interplay with foreign recognition and domestic perceptions plays a constitutive role in Russian foreign policy.

Furthermore, the ‘End of History’ did not annul the persistent factors which shaped Russian policy throughout history, namely its problem of “porous frontiers” as a multi-ethnic state (Rieber, 2010: 208). The historical challenge to keep control over its territory contributed to collective memory, creating a “fortress mentality” (Miller, 2016). Today, the popular saying ‘Russia has only two allies: its army and its navy’ by Alexander III is still well-known and, for example, exposed at the entrance of Moscow’s history park, Moya istoriya. A powerful alliance close to Russian borders has constituted a risk throughout history. At the same time, these factors pose a problem for accommodating Russian identity (and interests derived therefrom) in an alliance in which Moscow would have had to give up some authority.

Shifting leadership and political directions

Most notably, Russian foreign policy experienced two gradual shifts in its direction. The first was introduced by Gorbachev’s New Thinking and was marked by the subsequent pro-Western government under Boris Yeltsin. The Atlanticists were represented by Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev, who saw Russia as a European country and “NATO nations as our natural friends and future allies” (Forsberg and Herd, 2015: 44). This perception, however, did not represent public opinion, nor elite consensus. Although a growing number of Russians supported rapprochement with the West, the majority of Russians was wary of NATO and Western culture, demanding that the government counter America’s growing influence, which allegedly tried to turn their country into a second-rate power and mere supplier of raw materials (Levada Center, 2020; 2017; 2015). The still existing Supreme Soviet was dominated by nationalist and communist politicians (which led to Yeltsin’s shelling of the parliament). Thus, the liberal government faced a strong Soviet-educated elite advocating for an identity in distinction from Europe. Against this backdrop, Yeltsin replaced Kozyrev by the Eurasianist Yevgeny Primakov, who, in order to balance against the West, realigned Russia’s focus toward Asia and the former Soviet Republics. Primakov’s foreign policy doctrine called for ‘multipolarity’, opposing American hegemony (Ziegler, 2018: 130–31; Shin, 2009: 6–8).

At the same time, an anti-Russian lobby in the USA, which Tsygankov (2009: xiii) dubbed “russophobic”, tried to counter such developments by supporting the Russian Atlanticist opposition, pushing Cold War stereotypes and framing Russia as an inherently aggressive empire. Among them were prominent politicians like Dick Cheney, who stressed the significance to control Russian energy reserves, John McCain, and Joe Biden. Indeed, some sympathized with the idea of keeping Russia in its weakness (Tsygankov, 2009: 21–46). Zbigniew Brzezinski published an influential book, describing Eurasia as a “grand chessboard” on which the USA had to play well in order to preserve global primacy (Brzezinski, 1997: 1). Such political tendencies were unlikely to be overheard by Russian policymakers, hence the lobby might have reinforced anti-Western security bias in Moscow.

NATO and the Russian security dilemma

At the same time, NATO’s continued existence itself may have been the major reason why Western states did not show more inclination to the OSCE integration project. NATO turned out to be more powerful than ever before and the Baltic and Central-Eastern European countries actively sought to become members. Nevertheless, the first years after the fall of the Soviet Union have been described as a “honeymoon period” between NATO and the Russian Federation (Forsberg and Herd, 2015: 44). US Secretary of State James Baker even proposed that Russia should join the alliance (Forsberg and Herd, 2015: 43–45). At the beginning of 2000, Vladimir Putin still saw the possibility of a Russian membership, but stressed that he expected to be treated as an equal partner and that Russia’s interests should be reckoned with (Hoffman, 2000).

The notion of national interest and equal partnership, however, did not imply a ‘one state, one vote’ principle, but carried the veiled demand to grant Russia a veto right in security issues. Eventually, the honeymoon turned out to be a “dormant security dilemma” triggered by NATO’s Eastern expansion plans (Priego, 2019: 257-259). From the beginning, the unpopularity of NATO as a Cold War institution made Russia hesitant to join cooperation in which it was just granted the same status as Lithuania or Hungary. US President Clinton promised Yeltsin not to engage in NATO enlargements before Yeltsin had passed his parliamentary and presidential elections in 1995/96. In 1994, however, NATO announced a study for future memberships of Central and Eastern European countries as well as former Soviet Republics. This triggered Russian fears of an encirclement and created an anti-NATO consensus within the Russian government, including Yeltsin. Washington tried to mitigate irritations by establishing the Permanent Joint Council (PJC). Yet, this arrangement could not break Russian objection (Forsberg and Herd, 2015: 44–45). Obviously, Russia was the very reason for these countries’ urge to join the alliance – and therefore the prospective members undeniably shaped the character of NATO as a defensive alliance ‘against’ Russia. Thus, Russia’s inability to arrange good bilateral relations with its former allies must be seen as one crucial factor why no joint security structure could emerge.

The Permanent Joint Council, however, did not grant Russia the chance to influence political decisions, as it was bluntly disclosed by the exclusion of Russia from the formulation of NATO’s (1999) new strategic concept. Critically, the document permitted the organization to operate out of defence and out of the area, even without a mandate by the UN or OSCE (NATO, 1999). Nota bene, this undermined Russia’s opportunity to make use of its veto right within the UN Security Council, the only superior security structure. To make matters worse in the Russian perspective, NATO practised this violation of international law just one month later by bombing Russia’s ally, Serbia. After freezing relations and deploying troops to Kosovo, Russia eventually backed down and cooperated with NATO peacekeepers. Nevertheless, Russia rejected a NATO office in Moscow and kept cooperation on a minimum level (Forsberg and Herd, 2015: 45–46).

In his pro-European speech in the German parliament in 2001, in which he recalled the idea of Gorbachev’s Common European Home, Putin complained that old stereotypes from the Cold War remained:

“[I]n reality we have not yet learned to trust each other. […] Today decisions are often taken, in principle, without our participation, and we are only urged afterwards to support such decisions. After that they talk again about loyalty to NATO. […] Let us ask ourselves: is this normal? Is this true partnership?” (President of the Russian Federation, 2001).

In the following years, the PJC was substituted by a renewed format, the NATO-Russia Council (NRC). In fact, political cooperation increased especially around the issue of terrorism, which ushered a new momentum after 9/11. Russia participated in military exercises and welcomed the opening of a NATO office in Moscow; Putin praised progress (Forsberg and Herd, 2015: 47–48). The new council, however, remained symbolic in reality. New conflicts arose: Russia complained about the second round of NATO enlargement and NATO air control flights over Baltic states. Sergei Ivanov, Minister of Defence, publicly questioned the legitimacy of the persistence of a Cold War institution. On the American side, Senator John McCain publicly accused Putin of a coup against democracy and blamed him for challenging the territorial integrity of sovereign states in his neighborhood (Forsberg and Herd 2015: 48–49).

The accusation that NATO had broken its promise not to expand eastwards became a widespread myth, mostly brought forward by Russian diplomats. This allegation stems from the German unification process, when the membership status of a unified Germany was discussed under the initial assumption that NATO jurisdiction and troops would not expand to the territory of the GDR. By discussing a theoretical case in which a member of the Warsaw Pact sought NATO membership, the German Foreign Minister indeed considered generalizing this premise officially for any case of potential eastward movements. However, this idea did not prevail: Western governments deliberately never formalized any pledge of non-enlargement. At this time, no-one anticipated the implosion of the Soviet Union and subsequent dissolution of the Warsaw Pact (Sarotte, 2014; Gorbačev, 2015: 371). The discourse, nevertheless, highlights two crucial implications: First, Western actors were aware of the sensitive nature of NATO’s expansion. As Russia’s identity and legal status defined it as the Soviet Union’s heir, this sensitivity applied a fortiori for the post-Soviet space. The controversy among NATO partners in the 1990s expressed the continuing awareness: Clinton actually assured Yeltsin that no significant forces would be transferred into new territories (Forsberg and Herd, 2015: 45). However, the presumption of the ‘End of History’ and the intermediate loss of Moscow’s great power status superseded such cautious assessments. Second, as discussed above, history did not end, nor did Russian identity and security discourse. Even though factually incorrect, the Russian claim of a non-enlargement promise showcases a basic principle under which Russian elites operate. The Thomas theorem can be read as a warning: “If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences” (Thomas and Thomas, 1928: 572).

Conclusion

Russia was too big to be integrated on Western terms and, at the same time, too weak to assert its own terms. Its geographic vastness and richness in raw materials, alongside social collective memory and intellectual discourses, produce an identity which defines Russia as an inherently global power. The present economic and technological status does not matter here as much as the future potential. Though Russia had been closer to a developing country than a modern developed country in the 1990s, it could have been foreseeable that the largest country on earth would act as a temporarily halted superpower, given that it – against all odds in the Caucasus – did not further collapse. Under the centralized rule of Vladimir Putin, indeed, Moscow kept control over its territory and resources.

To conclude, four causal links, stemming from the above-analyzed factors, explain why the integration into a joint security structure, be it a new one like the OSCE or an updated NATO regime, failed:

- Russia did not develop the liberal state model which the West expected and called for. Therefore, NATO ignored Russian objections and sidelined its demands.

- Through this behavior, Russia was not treated in a manner consistent with its self-perception and potential power. The Russian request for an equal partnership of unequals was not accepted.

- Therefore, Russia did not accomplish its abstract interest (being treated as a superpower with a veto right), nor its material interests (e.g. Kosovo 1999, NATO enlargements), and thus started heckling these institutions. As a decisive matter, Russia failed to arrange and reconcile with its former allies and republics, which reinforced NATO as an alliance ‘against’ Russia.

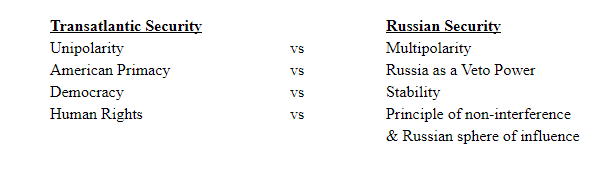

- As a result, two conflicting security concepts inhibited the emergence of a full integration beyond partial co-operation:

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brzezinski, Zbigniew. 1997. The Grand Chessboard. American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives. New York: Basic Books.

Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE). 1990. ‘Charter Of Paris For A New Europe’. Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE). https://www.osce.org/mc/39516?download=true.

Forsberg, Tuomas, and Graeme Herd. 2015. ‘Russia and NATO: From Windows of Opportunities to Closed Doors’. Journal of Contemporary European Studies 23 (1): 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2014.1001824.

Fukuyama, Francis. 1989. ‘The End of History?’ The National Interest, no. 16. Center for the National Interest: 3–18.

Fukuyama, Francis. 1992. The End of History and the Last Man. New York; Toronto: Free Press.

Gorbačev, Michail. 2015. Das neue Russland. Der Umbruch und das System Putin. Translated by Boris Reitschuster. Köln: Quadriga.

Hoffman, David. 2000. ‘Putin Says “Why Not?” to Russia Joining NATO’. Washington Post, 6 March 2000. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2000/03/06/putin-says-why-not-to-russia-joining-nato/c1973032-c10f-4bff-9174-8cae673790cd/.

Kramer, Mark. 1999. ‘Food Aid to Russia: The Fallacies of US Policy’. Policy Memo 86. PONARS Policy Memo. Program on New Approaches to Research and Security in Eurasia (PONARS Eurasia). http://www.ponarseurasia.org/sites/default/files/policy-memos-pdf/pm_0086.pdf.

Levada Center. 2015. ‘Russia & the West: Perceptions of Each Other in the View of Russians’. Yuri Levada Analytical Center. 13 August 2015. https://www.levada.ru/en/2015/08/13/russia-the-west-perceptions-of-each-other-in-the-view-of-russians/.

Levada Center. 2017. ‘Russia’s Relations with the West’. Yuri Levada Analytical Center. 9 January 2017. https://www.levada.ru/en/2017/01/09/russia-s-relations-with-the-west/.

Levada Center. 2019. ‘National Identity and Pride’. Yuri Levada Analytical Center. 25 January 2019. https://www.levada.ru/en/2019/01/25/national-identity-and-pride/.

Levada Center. 2020. ‘Russia and the West’. Yuri Levada Analytical Center. 28 February 2020. https://www.levada.ru/en/2020/02/28/russia-and-the-west/.

Levitsky, Steven, and Lucan Way. 2002. ‘The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism’. Journal of Democracy 13 (2): 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2002.0026.

Levitsky, Steven, and Lucan Way. 2010. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War. Problems of International Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

MacFarlane, Neil. 2001. ‘NATO in Russia’s Relations with the West’. Security Dialogue 32 (3): 281–96.

Miller, Alexei. 2016. ‘Memory Control. Historical Policy in Post-Communist Europe’. Russia in Global Affairs. 17 June 2016. https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/articles/memory-control/.

Nalbandov, Robert. 2016. Not by Bread Alone: Russian Foreign Policy under Putin. Lincoln, Nebraska: Potomac Books.

NATO. 1999. ‘The Alliance’s Strategic Concept Approved by the Heads of State and Government Participating in the Meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Washington D.C.’ North Atlantic Treaty Organization. http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_27433.htm.

President of the Russian Federation. 2001. ‘Speech in the Bundestag of the Federal Republic of Germany [Transcript]’. President of Russia. 25 September 2001. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/21340.

Priego, Alberto. 2019. ‘NATO Enlargement. A Security Dilemma for Russia?’ In Routledge Handbook of Russian Security, edited by Roger E. Kanet, 257–65. Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY.

Reuters. 1991. ‘SOVIET DISARRAY; Europe to Give Extra Food Aid to 3 Russian Cities’. The New York Times, 11 December 1991. https://www.nytimes.com/1991/12/11/world/soviet-disarray-europe-to-give-extra-food-aid-to-3-russian-cities.html.

Rieber, Alfred J. 2010. ‘How Persistent Are Persistent Factors?’ In Russian Foreign Policy in the Twenty-First Century and the Shadow of the Past., edited by Robert Legvold, 205–78. Columbia University Press. http://www.myilibrary.com?id=300889&ref=toc.

Sarotte, Mary Elise. 2014. ‘A Broken Promise? What the West Really Told Moscow About NATO Expansion’. Foreign Affairs 93 (5): 90–97.

Shin, Beom-Shik. 2009. ‘Russia’s Perspectives on International Politics: A Comparison of Liberalist, Realist and Geopolitical Paradigms’. Acta Slavica Iaponica, no. 26: 1–24.

Smith, Hanna. 2018. ‘European Organizations’. In Routledge Handbook of Russian Foreign Policy, edited by Andrei P. Tsygankov, 377–87. London; New York: Routledge.

Teltschik, Horst. 2019. Russisches Roulette: Vom Kalten Krieg Zum Kalten Frieden. Originalausgabe. München: C.H. Beck.

Thomas, William I., and Dorothy Swaine Thomas. 1928. The Child in America, Behavior Problems and Programs. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Tsygankov, Andrei P. 2009. Russophobia: Anti-Russian Lobby and American Foreign Policy. 1st ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tsygankov, Andrei P. 2012. Russia and the West from Alexander to Putin: Honor in International Relations. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ziegler, Charles E. 2018. ‘Diplomacy’. In Routledge Handbook of Russian Foreign Policy, edited by Andrei P. Tsygankov, 123–37. London; New York: Routledge.

Contact us

Become a contributor