SECOND EDITION

VOL TWOMona Ali

“A Solidarity of Fear?”: Risk Society Perceptions in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Countries Post-COVID-19

Abstract

The coronavirus pandemic has brought to the forefront the concept of “risk society”, first proposed by Ulrich Beck in the 1980s. Based on this concept, this paper attempts to analyse the ongoing changes to threat perception in the GCC region and the new risk culture formulated during the coronavirus pandemic in Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Qatar. The paper relies on a qualitative content analysis of a sample of writings by Gulf intellectual elites reacting to traditional and non-traditional threats in GCC countries, in order to identify changes in the features of risk-society perceptions in the GCC region.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Risk society, Qatar, UAE, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

On January 29, 2020, the first coronavirus infection in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries was announced in the UAE (Turak, 2020), followed shortly thereafter by Qatar’s announcement of its first case on February 29, 2020 (Reuters, 2020), and Saudi Arabia’s first coronavirus case on March 2, 2020 (Saudi Ministry of Health, 2020). Cases in the countries under study increased gradually to the degree that Gulf states’ governments initiated lockdowns and curfews and took extraordinary and unusual measures.

Considering this extraordinary situation, many sociologists have reconsidered the concept of risk society put forth by sociologist Ulrich Beck in the 1980s. Although Beck focuses specifically on the risks stemming from technological and scientific advances, some studies have already expanded the concept of risk society to a wider study of risks than he initially mentioned (Alauddin et al., 2020, p.502). This has encouraged social science theorists to apply the concept to the Coronavirus case (Covid 19), especially since much of what risk-society theorists have studied applies to the situation in post-pandemic societies.

This research paper attempts to apply the concept of risk society to three Gulf states—Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Qatar—focusing specifically on how Gulf intellectual elites have reacted to the post-pandemic risk society and their perceptions of the nature of the threats and the post-coronavirus shape of the world. This was done through a content analysis of opinion columns written by Gulf intellectuals, writers, and university professors.

The paper argues that the perception of risks and threats in GCC-countries has increased significantly following the outbreak of the Coronavirus pandemic. It also proposes that individuals in these societies have played a more active role in confronting these threats compared to the past, when states assumed responsibility for addressing such issues. These transformations have empowered and expanded the role of individuals and societies and have also brought greater attention to non-traditional threats.

Risk Society in the Literature

The idea of risk was brought to the forefront of sociological theorization in 1986 with the publication of Beck (1992)’s book, Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. Beck later presented many writings on risk society, and Anthony Giddens (1999) helped refine this concept.

The thesis of “risk society” has gained greater traction over time, especially given the complex and interconnected challenges that countries face. Modernity and the processes accompanying the shift from an industrial to a post-industrial society are associated with a set of global risks created by escalating scientific and technological activity. Paradoxically, in order to handle these risks, societies have a greater need for science and technology, which alone can provide the conceptual and technical tools that enable humanity to understand, identify, assess, classify, and protect against these risks (Boudia and Jas, 2007, p. 317).

Beck emphasised the historical nature of the existence of risks. According to Beck, risks are not a novelty of the modern age but have been with humans throughout various time periods. However, in the past, risks were personal rather than global (Beck, 1992, p. 21). Individuals have always faced risks, but fate (fatum) and chance (tyche) provided them with reasonable explanations for these risks. Another key difference between the risks of today and the past is that in the past, risks were perceived with the five senses, while today they are intangible. Beck argues, “It is nevertheless striking that hazards in those days assaulted the nose or the eyes and were thus perceptible to the senses, while the risks of civilization today typically escape perception and are localised in the sphere of physical and chemical formulas” (1992, p. 21).

There are also “environments of risk” that collectively affect large masses of individuals in some cases, and possibly everyone on Earth, as in the case of environmental disasters or nuclear war (Giddens, 1990). Risk society is a product of reflexive modernity. Society first went through the pre-modernity stage, known as ‘traditional society’, followed by the ‘simple modernity’ of the industrial society during which rapid industrial development and the accumulation of wealth appeared, and finally, ‘second modernity’, the period of ongoing industrial progress during which society faces many problems stemming from economic and technological advancement. The basic principle of industrial society is the distribution of goods. In contrast, the main principle of reflexive modernity is the distribution of “bads,” or dangers, such as pollution and contamination, etc. (Lash and Wynne, 1992, p.3). The word reflexive refers to a ‘boomerang’ effect, where mostly unplanned results of production processes in modern societies backfire on these societies and force them to change—certainly not a consciously planned chain of events (Wimmer and Quandt, 2007). By contrast, Anthony Giddens (1999) does not believe that society faces worse risks than previous societies but has become more desirous of controlling the future and more focused on achieving safety.

Beck and Giddens have faced several critiques of their focus on risks arising from technological advancement and scientific development. The first critique is that they ignore the many social benefits of science and technology. For example, Alan Irwin notes that Beck was overly critical of science and technology and insufficiently aware of the progressive potential of the new technologies. The second critique comes from Merryn Ekberg’s insightful study of risk society, in which he notes that risk-society theorists have pointed out that what distinguishes risk society is increased technological risks compared to natural risks. However, he notes that natural disasters, including epidemics and meteorological and geological disasters, cause greater loss of life and property damage than any technological accident (Ekberg, 2007, pp. 360-362).

Generally speaking, theorists have differed over the sources of threats in a risk society and whether there is intentionality in the creation and spread of risks. However, the tacit agreement among the majority of these thinkers is that there is a realisation of risks and an awareness even of those that have not occurred. Ulrich Beck notes that modern society has become increasingly preoccupied with discussing, preventing, and managing the risks that it has produced. The matter is further complicated within what Beck calls a “world risk society” and de-localization, meaning that the causes and consequences of risks are not limited to a geographical location or defined space (Beck, 2006, p. 333).

Moreover, limiting incalculableness, in one form or another, reduces the consequences and effects of risks. The third principle depends on non-compensability in the event of a disaster or risk. In this context, the principle of “precaution through prevention” is pushed as an alternative to the logic of compensation. The main goal is to attempt to anticipate and prevent unverified risks (Beck, 2006, p. 334).

Despite all the scientific progress and technological development, a state of uncertainty prevails that negatively affects awareness of and preparation for potential risks—or what some literature calls “uncertain risk” to refer to the uncertainty regarding the presence or absence of risks (Jansen et al., 2019, p.659).

In a risk society, everyone faces risks equally, regardless of class. Beck believes that this is because of the boomerang effect, where even the wealthiest people and those who benefit the most from the production of risks cannot escape risk society because shrinking “private escape routes” create equality between the rich and the poor (Curran, 2013, p. 48). However, Beck contradicts himself when he notes that “Poverty attracts unfortunate abundance of risks” (1992, p. 21). Furthermore, according to Beck, risk society refers to a global distribution and shared experience of risks, which is not reflected in contemporary reality because the global distribution of “bads” appears unequal and disproportionate among nations (Mythen, 2007, pp.799-800). Notwithstanding the criticisms directed at Beck in this regard, he drew attention to the fact that no one is completely safe from risks, which leads to a solidarity of fear rather than a solidarity of need (Tavares and Barbosa, 2014, p.22).

Although science and knowledge could be the main exit from risk society, there is a loss of faith in experts and the ability of science to predict and effectively protect people from these technological risks. Competing claims of knowledge increase the state of doubt, the so-called ‘erosion of expert consensus’. In short, scepticism towards science arises, in particular with individuals’ awareness of the limits of science (Baxter, 2019, p.305). Fear of those who talk about risks, and not of the risks themselves, is called “scapegoat society,” wherein, as Ulrich Beck (1990, p. 68) describes it, “the general anxiety shifts its focus from the risks to those discussing those risks.”

Lucas Bergkamp argues that the rise of the risk society represents a crisis in effectively managing risk with a focus on how to distribute risks, and it misdirects resources because of a lack of adequate risk prioritisation, giving birth to the problem of NIMBY-ism, not to mention the crisis of the legitimacy of science in our society. Thus, Bergkamp (2016, pp.1287-1289) believes that the threat comes from the risk society itself: “The risk society is a dead end. Rather than industry, the real threat is risk society itself.” This means that the real threat comes from the shortcomings of risk society itself and its inability to adapt to internal and external changes, thus increasing its vulnerability.

Features of Risk Society in the Arab Gulf States

The coronavirus pandemic can be considered a decisive turning point in the vision needed to react to risks in the Arab Gulf region, where, for decades, traditional security threats have been the most pressing concern of decision-makers and public opinion makers vis-à-vis the survival, cohesion, and territorial integrity of states. While non-traditional security threats were not new to the Arab Gulf states, they ranked relatively low among the threats to national security in most of these countries due to the presence of more urgent threats from the viewpoint of the ruling regimes, such as the Iranian nuclear program and the development of Iranian military capabilities—especially ballistic missiles and drones, the activities of sectarian armed militias, disputes over regional primacy, the expansion of political Islam and terrorist organisations, and other security and military threats (Arafat, 2020, pp. 199-200).

The unique situation of ‘risk society’ in the Arab Gulf following the coronavirus pandemic put non-traditional security threats at the forefront. The statement of Mohammed bin Zayed, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, in March 2020—to the effect that “medicine and food are a red line in the UAE that must be secured for our people indefinitely” (UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, 2020)—perhaps reveals a growing attention to non-traditional security threats and a rising focus on health and food security amidst the turmoil in the medical and food supply chains at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic.

The other key dimension of change in the state of risk society during the coronavirus pandemic is the rising role of individuals in facing non-traditional threats compared to the state’s previous dominance in confronting traditional security threats. Numerous groups were empowered and considered the “first line of defence” in facing coronavirus threats, including healthcare workers and volunteers in hospitals and nursing homes (SEHA, 2020; Saati, 2020). Individuals became responsible for stopping the outbreak of the pandemic by following preventive measures and adhering to safety instructions.

In May 2020, within the framework of its plans to counter the coronavirus outbreak, the UAE launched an awareness campaign under the slogan, “You Are Responsible.” The campaign focused on warning of the negative impact of individuals and families failing to comply with procedures and instructions. It also called on society to maintain the gains that had been achieved since the beginning of the crisis by adhering to precautionary measures (Amin, 2020).

The responsibility of individuals and society in combating the coronavirus pandemic was reflected in the statements of Dr. Farida Al Hosani (2021), Director of the Department of Communicable Diseases at the Abu Dhabi Public Health Center, in May 2021, on the responsibility of vaccine-hesitant members of the community for the increasing number of infections, stressing that “the delay of some members of the community in getting the vaccine harms the person and those around him.”

In the same vein, the Center for Government Communication at the Saudi Ministry of Information launched new awareness campaigns to combat COVID-19 in January 2022, as an extension of the “We Are All Responsible” and “We Return With Caution” campaigns. The new Saudi campaign, under the slogan “Our Immunity Is Life,” urged individuals to get the vaccine and booster doses with the goal of returning to everyday life. The identifying colours merged green with blue as an expression of society’s solidarity in implementing precautionary measures to reach full immunity (Saudi Center for Government Communication, 2022).

Although individuals and communities bore significant responsibility during the period of combatting the pandemic, leadership for managing the crisis and confronting the pandemic remained the exclusive domain of the state and its safety and health authorities. Committees and institutions for managing the crises and health emergencies established rules and imposed controls and precautionary measures for combatting the pandemic, and individuals were responsible for following these rules, otherwise, harsh penalties would be imposed on them for exposing the community to risk (UAE Ministry of Labor, 2020; CNN Arabic, 2021).

State control was strengthened by the expansion of monitoring and tracking mechanisms and societal acceptance of using various tools to monitor compliance with precautionary measures. Surveillance cameras were deployed in public places to monitor those failing to comply with mask-wearing. Tracking devices were used to ensure that infected people were quarantined in their homes until they had recovered. Health applications were also used to track cases, contacts, and rates of and timely doses of anti-coronavirus vaccines. In other words, this strengthened the state’s authority and ability to control the behaviour of individuals during the pandemic (France 24, 2020).

There are several indicators of the high degree of confidence in the state’s response to the coronavirus pandemic, including many videos on social media of citizens and expatriates enthusiastic about the UAE’s national activity and expressing their appreciation for the state’s efforts to protect them (AlArabiya.net, ‘Shāhid,’ 2020). Qatar and Saudi Arabia also witnessed similar phenomena (AlArabiya.net, ‘Min shurafāt al-manāzil,’ 2020). There was also relative acceptance of the authorities’ management of the flow of information, starting with statistics on cases and deaths, continuing through the status of the outbreak of the virus and the prevention measures to be followed, and ending with the imposed treatment protocols and procedures for dealing with chronic cases. This can be compared to other countries that witnessed societal rebellion against the state’s knowledge-based authority during the pandemic, whether by adopting alternative treatment protocols, rejecting precautionary and preventive measures, questioning the safety of vaccines and their side effects on public health (CDC, 2021), or even politicising the reaction to the pandemic or transferring political divisions to the handling of the coronavirus outbreak (Durkee, 2021).

Citizens’ and residents’ demand for experiments to test the effectiveness of vaccines in the UAE, for example, is evidence of their confidence in state institutions. Large numbers volunteered to test Russian and Chinese vaccines in the UAE, without coercion from the state, despite being in the initial stages of development (Emirates News Agency, August 2020)—especially since the terms and conditions of the experiments held individuals responsible for taking the vaccines in accordance with the declarations signed by them (Bayoum, 2020). Moreover, vaccination rates have reached record levels in several Arab Gulf states. In the early stages, this also reveals the acceptance of the state’s health authority over individuals (National Emergency Crisis and Disasters Management Authority, 2022; Qatar Ministry of Public Health, no date).

Post-Pandemic Threats to the Gulf States

In order to understand how intellectual elites in the Gulf perceive COVID-19 threats and risks, this paper’s author conducted a content analysis of opinion columns by Gulf writers in the most widely-circulated digital newspapers in three countries: Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar.

Two newspapers each were chosen from Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE based on the most-visited news sites for each country (as per statistics on site traffic generated by Similarweb, which ranks websites from different countries by the number of visitors), excluding papers that lack a full electronic archive of their opinion columns or which do not publish opinion columns. Based on these criteria, the following newspapers were selected: al-Ittihad and al-Khaleej (from the UAE), al-Raya and al-Sharq (from Qatar), and Okaz and al-Riyadh (from Saudi Arabia)

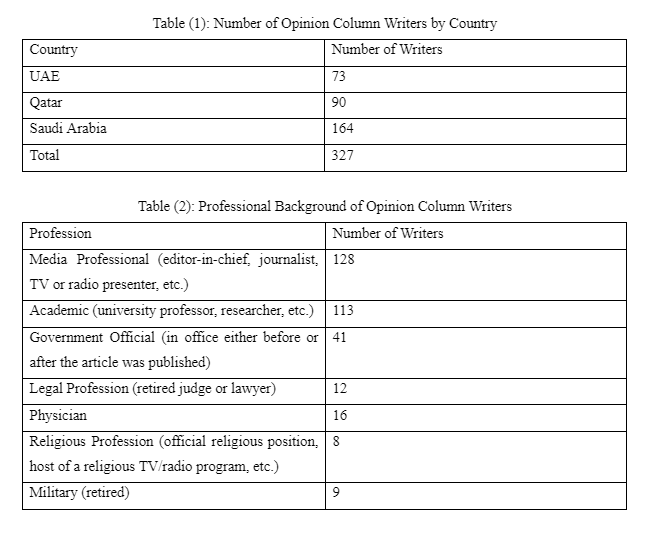

The content analysis was conducted on columns published during the period between 29 January 2020—when the first COVID-19 case was recorded in the Gulf (in the UAE) (Emirates News Agency, January 2020)—and May 2022. There were 903 articles included in the study. Table (1) shows the number of Emirati, Qatari, and Saudi writers whose articles were included in the content analysis, while Table (2) depicts the professional background of the articles’ authors.

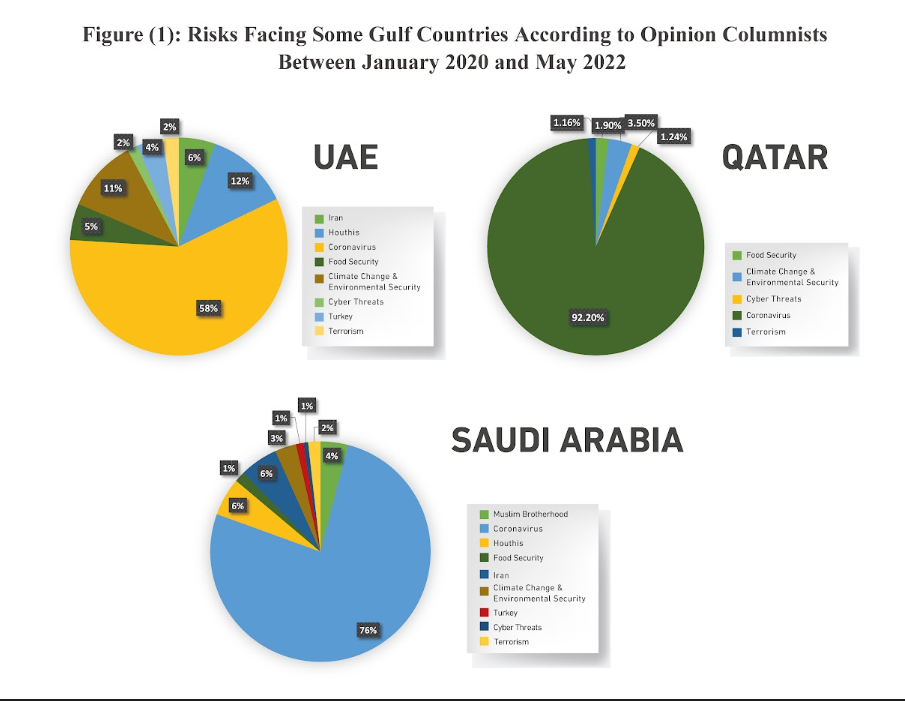

Source: Graphics made by the author based on articles collected from six Gulf newspapers.

Figure (1) shows the number of opinion columns by Gulf writers discussing security risks and threats in articles published during the aforementioned period of time. COVID-19 risks and threats were the main area of focus, and were the subject of 58 percent of articles discussing security risks in the UAE, 92.2 percent of articles in Qatar, and 76 percent articles in Saudi Arabia during this period.

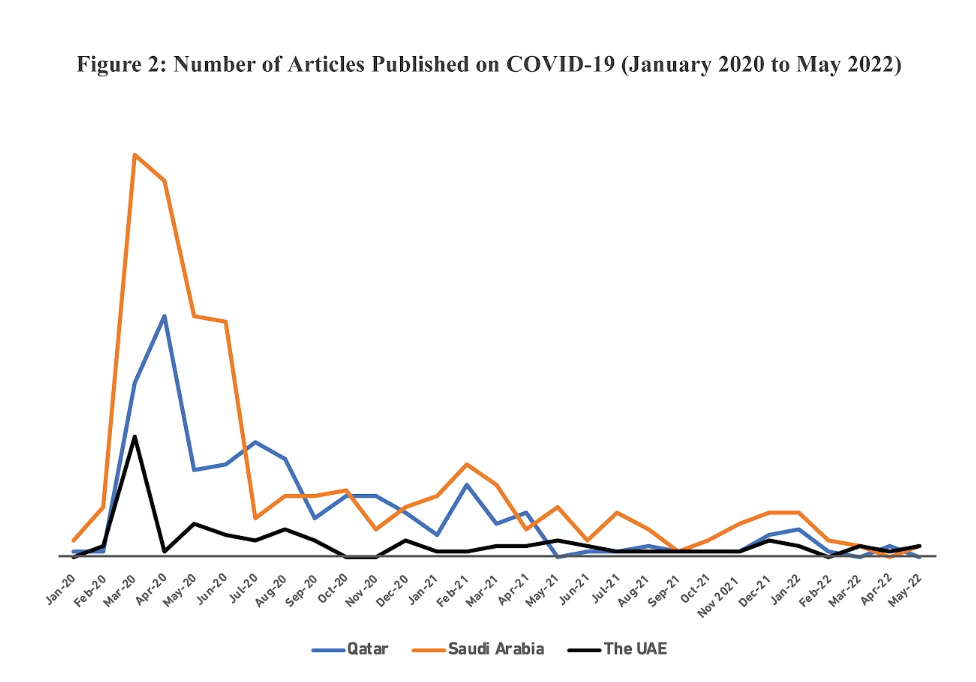

Most of these articles were written between February and June 2020, when COVID-19 first emerged as a threat. Generally speaking, the number of articles discussing the threat of COVID-19 increased during the initial phases of the pandemic, and then decreased as people became more accustomed to living with the virus, as shown in Figure (2) below.

Despite the increasing focus on the threat of COVID-19 in opinion columns, traditional threats remained important issues of discussion. Articles published on traditional security issues in the UAE made up 24 percent of articles on security issues during this period. In the UAE, traditional security issues included Iran, the Houthis, terrorism, and Türkiye during a period of tension between the UAE and Türkiye, especially in Libya. In Saudi Arabia, traditional security threats comprised 16 percent of all opinion pieces on security risks; these threats included the Muslim Brotherhood, the Houthis, Iran, Türkiye, and terrorism. In contrast, the only traditional threat discussed in Qatari opinion columns during the period in question was terrorism, which comprised only 1.16 percent of Qatari articles included in the study.

Source: Graphics made by the author based on articles collected from six Gulf newspapers.

In all three countries, the expanded focus on COVID-19 was accompanied by growing concerns about other nontraditional security issues, including food security, climate change and environmental risks, and cyber security. These issues were less prominent relative to the threat of COVID-19. Most of the traditional and non-traditional security issues that preoccupied Gulf opinion columnists were similar to those dominating official Gulf discourse during this period. These other security issues existed before COVID-19, but the pandemic prompted opinion columnists to focus more on COVID-19. However, other risks and threats remained a topic of concern. This aligns with British sociologist Hilary Rose’s argument that Ulrich Beck was “overly optimistic in assuming that pre-risk society risks have disappeared” (Ekberg, 2007, p. 360). In reality, risk society coexists with pre-risk society to form a hybrid society that includes a debate among the different attitudes toward the priority of traditional and non-traditional threats and risks.

Gulf Intellectual Elites’ Reaction to the Risks of Coronavirus

According to many writers, Covid 19 represented a turning point and the end of the safe era. For example, Emirati researcher Salem Salmin Al Nuaimi (2021) pointed out that “the global coronavirus pandemic is the culmination of the era of risks and the end of the safe era. Everything has become a danger and a threat.” Saudi writer and assistant professor of the history of Islamic civilization, Abdullah Al Rashid, cites Anthony Giddens to the effect that our world is seeing risks never before faced in the past. Al Rashid agrees with Giddens, noting that, despite scientific progress, people are losing control of the Earth, day by day. According to Al Rashid, the greatest question that must be asked is, “Were the tsunami in the Indian Ocean, the tsunami in Japan, the spread of coronavirus, and the like, merely natural occurrences or the result of human misuse of the resources of planet Earth?” He also poses another question: “Are floods, earthquakes, epidemics, famines, and droughts natural events or the result of human influences that have led to the disruption of Earth’s balance?” (Rashid, 2020).

Many opinion columnists adopted conspiracy theories and narratives lacking scientific evidence because of information failures in the initial stages of the Covid 19 outbreak. For example, the Saudi journalist and media affairs researcher Badr bin Saud (February 2020) implicitly accused the United States of being responsible for spreading the virus as part of its efforts to curb China’s rise.Qatari writer Abdullah Al Emadi (2020) believed that coronavirus might have been manufactured to achieve gains for a select few globally, perhaps in the form of countries, transnational corporations, or the like. The Saudi writer, Ahmed Awwad (2020) agreed with him, pointing out that coronavirus may have been leaked from a medical laboratory or spread by a country’s intelligence services to achieve specific goals.Some writers thought that Covid-19 might be natural but speculated that the virus would be used against third-world peoples and that secret arrangements for dividing gains between the Western countries might be carried out in the post-coronavirus world (Flamerzi, 2020). Some conspiracy theories were politicised: for example, the former editor-in-chief of Asharq Al-Awsat newspaper, Mohammed al-Saed (2020), indicated that Turkish President R.T. Erdogan intentionally spread coronavirus into Europe through an elaborate plan.Most of these articles were published amid the initial confusion surrounding the emergence of the coronavirus pandemic. Conspiracy narratives usually spread with each occurring crisis and epidemic. An atmosphere of fear, ignorance, uncertainty and chaos prompts some individuals to seek out the secret, or even known, party behind the crisis to spin an explanatory story that creates meaning for them amid the events and daily interactions in times of epidemic (Ali, K.H., 2020). On the other hand, some articles maintained a degree of rationality in explaining the epidemic and tried to refute conspiracy theories with logic, especially since the GCC governments were characterised mainly by rationality and the debunking of myths (Makki, 2020; Mohannadi, October 2020; Awadi, 2020).

Given the absence of clear explanations and practical solutions on the part of science, especially in the early stages of the pandemic, some opinion writers were sceptical of the science and experts due to the conflicting opinions of experts and the World Health Organization when coronavirus first emerged. For example, Saudi journalist Emad Al Abbad (2020) noted that “at the beginning of the coronavirus crisis, the world turned to the WHO as the most important authority for handling such pandemics that threaten human health…What it published became the sole guide for dealing with the epidemic, given its expertise and the large army of experts working with it. However, this confidence in the WHO shifted to doubt and distrust because of the obvious confusion in its messaging.”

Similarly, Abdulla Al Suwaiji, the director of the Higher Colleges of Technology in Sharjah, gave several examples of how the WHO’s confused statements and exaggeration frightened people. For example, the WHO suggested that Covid 19 is transmitted by touching contaminated surfaces, and it overstated its reassurance by declaring that those infected with the virus acquire long-term immunity. The WHO later had to retract these statements (Suwaiji, 2021).

Scepticism towards experts is not due solely to their conflicting opinions. It is also caused by the perception that they are attempting to serve the interests of certain actors. For instance, Qatari writer Aisha Al Obaidan (2022) claimed that the fourth shot of the vaccine was being promoted to serve the interests and increase the profits of the companies producing these vaccines. Some opinion writers worried that science was being forcibly injected to achieve political ends that serve the interests of certain countries and major institutions. Despite the media’s attempt to push for a return to normal, its focus on societal fear and anxiety turned it into a greater spreader of fear than the coronavirus itself.

People seek solace in religion during difficult and uncertain times. Many columnists opined that the solution to the crisis could be found in God; some considered the pandemic a test from God; and many used religious slogans, Quranic verses, and hadiths of the Prophet (Yamani, N., March 2020; Hilabi, 2020; Shamsi, 2020, Jassem, 2020; Ishaq, M., 2021). Religious slogans were used to emphasise that adherence to preventive measures was a matter of obedience to the ruler and should not be violated. Likewise, stories from Islamic heritage were used as evidence that quarantine is a prophetic Sunnah or tradition, that must be followed, and that adherence to the government’s precautionary measures is the essence of Islam in warding off corruption and preserving oneself (Nuaimi, May 12, 2020; Dari, 2020; Shahwani, 2021; Anzi, 2021). With the emergence of the coronavirus, the turn to religion increased in various countries throughout the world (Pew Research Center, 2021). Some studies show that, during crises, religion helps individuals cope with and resist the insecurity spreading around them and that religious narratives help overcome the present moment and accept the current situation (Meza, 2020, p.220).

Conspiracy narratives and doubt in experts have gradually begun to recede, especially after the Gulf states managed the coronavirus crisis more effectively than many other major countries (Rossi and Kabbani, 2020). The Gulf states used their financial resources early on to combat the pandemic and deployed surveillance systems to track and control cases of the disease. They were also able to impose lockdowns without public opposition, given that the Gulf states could control food reserves and medical resources (Lynch, 2020, p.3).

The writings of Gulf intellectual elites reflected support for the state’s official discourse on the pandemic, confidence in the scientific opinion issued by the state’s experts (Tunaiji, 2020; Shaiba, 2020; Shamrani, 2020; Saad, March 2020), and the spread of nationalist discourses confirming the excellence and uniqueness of the Gulf states in managing the crisis. Coronavirus represented an opportunity to eliminate the West’s “superiority complex,” especially in the former colonising countries (Talib, March 20, 2020). Many writers made comparisons between the Gulf states and the developed Western countries, noting that the former were able to outperform the latter in their ability to contain the disease and reduce the number of deaths. For example, the Saudi writer and television host Khalid Al-Sulaiman (2021), noted that “Saudi Arabia came out of the coronavirus pandemic ahead of first-world countries!” This tendency to prove superiority over Western countries can be explained by the desire to show the legitimacy of the achievement and the state’s ability to lead society during the pandemic compared to other countries. A sense of reassurance also comes from superiority over others and better results than countries that are considered the measure of progress in medical care globally.

Likewise, the Qatari writer, Ahmed Al Mohannadi (April 2020), stated that “For the first time, I do not see the West doing more than us in dealing with coronavirus, and perhaps less than us…For the first time, I see the West recognizing and thanking us for what we are doing for them.” Emirati writer Sultan Al Jasmi (2020) pointed out that the UAE has become the most suitable country in which to live post-coronavirus due to its ability to manage this battle successfully, and that the virus represented an opportunity for the UAE to establish its leadership through the humanitarian assistance it offered to other countries during the pandemic (December 2021).

Attention to the human dimension was not limited to foreign countries but also included a focus on solidarity and the individual’s responsibility for the health security of the group. The role of individuals is central to the Gulf states’ coronavirus strategy, which prompted some of these countries to launch slogans like “We Are All Responsible,” “We Return With Caution,” and other such slogans that indicate that fighting coronavirus is the joint responsibility of the state and the community (Ali, M., 2020). In this context, many articles were critical of individuals who violated precautionary instructions and measures, exposed others to risk, or behaved irresponsibly by spreading rumours and circulating news on social media without confirming its authenticity (Otaibi, 2020; Wabel, 2020; Daoud, 2020, Jasmi, January 2021; Jasmi, June 2021). Some writers described compliance with precautionary measures as a national duty (Anzi, 2021; Kuwari, K., 2021), with one of them going so far as to call violators of precautionary measures traitors to the nation (Saad, June 2020). Some articles called for harsher legal penalties against those who violate precautionary measures or conceal coronavirus patients (Kaabi, 2020; Sulaiti, 2021; Kuwari, R., 2021), and the publication of the violators’ names, job details, and specialisations (Mulla, 2020).

This relates to the individual as the centre of risk society, as the end and the means at the same time. The individual is exposed to threats and is the main actor who is able to confront them. Individualism becomes an essential feature in risk society, making the decisions of individuals highly influential on society. This individualism increases as a result of experts’ failure to manage risk. Moreover, political institutions sought to promote the alignment of individuals against threats due to their institutional inability to find solutions apart from directing the choices of individuals. Hence, the focus on appealing to individuals to take responsibility and show discipline in confronting the pandemic emerges because the well-being of society, according to political institutions, depends on an endless series of individual choices (Mythen, 2005, p. 132; Beck, 2009, pp. 7, 54-55)

Gulf Intellectual Elites’ Perceptions of the Post-Coronavirus World

From the first weeks of the spread of coronavirus, many articles were published on the post-coronavirus world. The prefix ‘post’ dominated many articles about the virus, even though the state of emergency and lockdown caused by the pandemic had not yet ended. These articles discussed all the expected impacts of coronavirus on all aspects of life, lifestyles, education, values, the health sector, etc. The focus of this section is on opinion writers’ perceptions of the post-coronavirus world regarding the coming risks and threats and regional and international interactions.

The coronavirus epidemic caused many opinion writers to be more attentive to non-traditional threats. They feared that coronavirus represented the emergence of a new pattern of biological threats. They also speculated that biological warfare could replace traditional warfare (Bin Saud, February 2020), especially because biological weapons are available for manufacture in the major countries without the capacity for the mutual deterrence of conventional wars. Saudi writer Talal Saleh Banan (2020) projected that the next world war would be biological:

“The choice to use biological weapons is available, especially in the major countries. Efforts are focused on developing viruses with greater lethality, a longer incubation period, and precise genetic selection ability to select their targets and infect specific human races, and on developing antivirals to be used selectively during an epidemic, or even before or during biological warfare.”

The Emirati researcher, Salem Salmin Al Nuaimi, expected that an era of “biotechnology terrorism” was beginning, which will use cyberspace to achieve its goals of disturbing biological security. Terrorists may attempt to penetrate water and irrigation networks or research centres specialising in the study of viruses and bacteria (Nuaimi, 2021). In general, coronavirus has made opinion writers attentive to the next epidemic or pandemic, whether it is spread by certain actors to achieve specific interests, or naturally (Nuaimi, August 2020; Bin Saud, May 2020).

Thus, some writers have called for a national biological security strategy that builds defence capabilities that are ready and able to combat and keep abreast of biological risks in the event of an intentional attack or accident, foresight systems for virus-related threats, and increased spending in the health sector (Hamza, 2020; Morished, 2020).

This means the transformation of the coronavirus pandemic, in their perception, from a threat to health security into a traditional security threat. The latter requires a military strategy in the framework of expanding the securitization of non-security phenomena and environmental and biological threats resulting from the interaction of individuals with the surrounding environment. Saudi writer Hammoud Abu Talib called for the establishment of a global health security council with the ability to issue decisions under Chapter 7 that require the use of force if countries fail to enact emergency procedures when an epidemic spreads (Talib, March 13, 2020).

All the writers consulted agreed that the coronavirus represents a decisive turning point in the international order and that the issues and crises that accompanied it pose new challenges to the international order and cast doubt on the ability of the current international institutions to address major crises, including the economic crisis that followed (Khashaiban, 2020; Makki, March 2020). In this respect, Qatari writer Iman Abdul Aziz Al Ishaq (2020) noted that “shrinking expectations of growth rates, economic stagnation, stagnant markets and stock exchanges, and the inability to predict the future will accelerate the drawing to an end of modern history.”

There was near consensus that the new international order will be multipolar and will witness the rise of the role of China and Russia and an increasing desire of European countries for independence from the United States (Makki, August 2020; Nuaimi, 2022; Ishaq, I., 2020). Saudi thinker Youssef Makki (August 2020) predicted that European leaders would draw closer to the countries of the East in their search to find an alternative to Washington. Overall, the map of international alliances will change, which will have an impact on the region’s crises.

Some writers believed that the coronavirus would call into question isolationism and restore regard for multilateralism, such as Deputy Prime Minister and official spokesman for the Qatari Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Majed Mohamed Al-Ansari (2020). On the other hand, Emirati researcher Salem Salmin Al Nuaimi (2022) and Qatari writer Iman Abdul Aziz Al Ishaq (2020) argued that the globalist system will face many challenges in addition to the rise of right-wing nationalist movements and the declining ability of international organisations to impose their rules.

Some writers put forth proposals for the Gulf states to have an influential presence in the new international order. For example, retired Emirati Major General Abdullah Al-Sayed Al-Hashemi (2020) called for the drafting of a plan for rebuilding the world and transitioning to a new post-coronavirus world order, noting that the UAE’s leadership of reconstruction efforts in the Middle East represents a care pillar of this plan. Saudi writer Mashari Al-Naeem (2020) also pointed to the need to develop scientific research systems and technological development in order for the countries of the region to have an important presence in the new world order.

These visions reveal the perceptions of a general consensus that a change in the international order is inevitable and necessary in order to adapt to the changes resulting from the coronavirus pandemic. According to previous perceptions, the new world is characterised by multipolarity, the rise of non-Western powers in the world order, and the changing map of international alliances. Furthermore, the world is divided between two approaches, one pushing towards isolationism and the other towards further globalisation. The perceived role of the GCC countries is to support the coming scientific and technological revolution and to benefit from its returns in strengthening its position in this new global order.

Conclusion

Opinion columnists’ perceptions of the coronavirus world were a typical application of what Ulrich Beck imagined about risk society, since, in the early stages of the emergence of coronavirus, a state of uncertainty and scepticism towards science spread in light of its inability to deal with the pandemic effectively in the initial stages. Likewise, there was loss of faith in experts, and some instead adopted conspiracy theories or resorted to religion as a safe haven in the midst of chaos.

This state of confusion was reflected in the behaviour of some individuals who violated the precautionary guidance and instructions for coronavirus and spread rumours and panic among the rest of society, prompting Gulf intellectual elites to demand that more restrictions and tighter control be placed on individuals and their movements. By contrast, they praised the conduct of the Gulf-state governments, which was characterised by guidance and quick reaction in dealing with the crisis. Contrary to the perceptions of risk-society theorists of the existence of a central role for individuals in the face of hazards, and although the strategies of the Gulf-state governments placed responsibility on individuals for the first time to combat risks and threats, the chaos and confusion among members of society led to a lack of confidence in the judgement of individuals and gave more power to the already powerful Gulf states.

In contrast to Beck’s implicit assumption of risk society as a permanent state in which society remains inextricably bound, it is clear from a review of the writings of Gulf intellectual elites that there is an ongoing pursuit of coexistence, the development of mechanisms to return to the pre-risk society, and an attempt to restore confidence in science and technology and eliminate the chaos that prevails amid disasters. Risk society makes individuals more aware of future threats and risks and more attentive to similar threats, which is consistent with the views of risk-society theorists. Individual imagination is also active in imagining risks and developing scenarios for hazards that have not previously occurred, wondering about the extent of their possibility in the future, and demanding proactive measures before the next disaster occurs. According to the content analysis of the writings of Gulf intellectual elites, risk society makes individuals more aware of non-traditional threats. Future researchers will find a fertile ground of inquiry in exploring and analysing these GCC elites’ views and of their counterparts in other regions of the world opening that the advent of the risk society constitutes the turning point of the current world order, after which the form and scope of threats differ and the nature of relationships between states and international balances of power irreversibly changes.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Al-Abbad, E. (2020) ‘Al-dars al-qāsī li-munaẓzama al-ṣiḥiya al-‘ālamiya,’ Al Riyadh, 24 August. Available at https://www.alriyadh.com/1838351

AlArabiya Net (2020, March 28) Shāhid: muqimūn yuraddidūna nashīd al-imārāt li-l-tadamun ma‘a ḥamlat Corona. Available at https://bit.ly/3QmGCfb

AlArabiya Net (2020, March 29) Min shurafāt al-manāzil: nashīd al-waṭanī yasḍaḥu fī samā’ al-Sa‘ūdiyya. Available at https://bit.ly/3xYlRiI

Alauddin, M., Silmi, F.A., Prayogi, A.N., and Sunesti, Y. (2020) ‘Postmodern vision on COVID-19 outbreak: a risk society experience in Surakarta,’ Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research: 6th International Conference on Social and Political Sciences, 510, pp.501- 507.

Ali, K.H. (2020) ‘Dhihniyāt al-awbi’a,’ FUTURE for Advanced Research & Studies, 12 April. Available at https://futureuae.com/ar-AE/Mainpage/Item/5500

Ali, M. (2020, September 17) ‘COVID-19 crisis management: lessons from the GCC countries,’ Paper presented at web forum on New Threats, New Movements, New Nationalism: The Risks and Securitization of Covid-19, International Political Science Association, IPSA Research Committees on Security, Conflict, and Democratization (RC 44).

Al-Saed, M. (2020) ‘Hal nashara al-saffāḥ Erdogan Corona fī Ūrūbā?’ Okaz, 30 March. Available at https://www.okaz.com.sa/articles/authors/2017352

Amin, M. (2020) ‘#Anta_mаs’ul: ḥamla ilaktrūniya li-l-ḥadd min Corona fi-l-Adha,’ Emarat Al Youm, 27 July. Available at https://www.emaratalyoum.com/local-section/other/2020-07-27-1.1380251

Ansari, M.M.(2020) ‘‘Ālam mā ba‘d Corona,’ Asharq, 7 December. Available at https://bit.ly/3bcVSLg

Anzi, A.R. (2021) ‘Iltizām bi-l-tadābīr al-iḥtirāziya wājib waṭanī,’ Al Raya, 9 February. Available at https://bit.ly/3bksRgS

Arafat, A. (2020) Regional and international powers in the Gulf security, Palgrave Macmillan.

Awadi, A. (2020) ‘Corona: al-tarkīz ‘alā al-wiqāya,’ Al-Ittihad, 12 March. Available at https://bit.ly/3OC2SzT

Awwad, A. (2020) ‘Corona mawtun qādim, yā wizārat al-ṣiḥiyya,’ Okaz, 28 January. Available at https://www.okaz.com.sa/articles/authors/2007586

Banan, T. (2020) ‘Al-ḥarb al-kawniya al-thalitha (biyūlūjīya)!’ Okaz, 3 March. Available at https://www.okaz.com.sa/articles/authors/2013220

Baxter, J. (2019) ‘Health and environmental risk,’ International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp.303-307.

Bayoum, A. (2020) ‘Ṣiḥat Abu Dhabi tudashshin al-tajārib al-sarīriya li-laqaḥ Corona,’ Emarat Al Youm, 16 July. Available at https://www.emaratalyoum.com/local-section/health/2020-07-16-1.1376081

Beck, U. (1990) ‘On the Way Toward an Industrial Society of Risk?’ International Journal of Political Economy, 20(1), pp.51-69.

Beck, U. (1992) Risk society: towards a new modernity, translated by Mark Ritter, London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Beck, U. (2006, August) ‘Living in the world risk society,’ Economy and Society, 35(3), pp. 329- 345.

Beck, U. (2009) World at risk, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bergkamp, L. (2016, March) ‘The concept of risk society as a model for risk regulation – its hidden and not so hidden ambitions, side effects, and risks,’ Journal of Risk Research, 20(10), pp. 1275-1291.

Bin Saud, B. (2020) ‘Al-‘ālam sayamraḍu mā lam tata‘āfi al-ṣīn,’ Okaz, 3 February. Available at https://www.okaz.com.sa/articles/authors/2008551

Bin Saud, B. (2020) ‘Corona maraḍ ish‘ā‘ī,’ Okaz, 9 March. Available at https://www.okaz.com.sa/articles/authors/2014158

Bin Saud, B. (2020) ‘Corona ṭā‘ūn al-‘ālam al-jadīd,’ Al Riyadh, 14 May. Available at https://www.alriyadh.com/1821067

Boudia, S. and Jas, N. (2007, December) ‘Introduction: risk and ‘risk society’ in historical perspective,’ History and Technology, 23(4), pp.317-331.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2021, April), Estimates of Vaccine Hesitancy for COVID-19. Available at https://data.cdc.gov/stories/s/Vaccine-Hesitancy-for-COVID-19/cnd2-a6zw/

CNN Arabic (2021, May 11) Saudi tu‘addil jadwal al-‘aqūbāt mukhālifat ijrā’āt muwājihat Corona, ilaykum al-qā’ima. Available at https://arabic.cnn.com/middle-east/article/2021/05/11/saudi-covid-restrictions

Curran, D. (2013) ‘Risk society and the distribution of bads: theorizing class in the risk society,’ The British Journal of Sociology, 64(1), pp.44-62.

Daoud, A.M. (2020) ‘Ba‘d al-‘awda: al-wiqāya mas’ūliyatunā jamī‘an,’ Al Riyadh, 24 June. Available at https://www.alriyadh.com/1828177

Dari, O.H. (2020) ‘Multazimūn yā waṭan,’ Al-Ittihad, 29 March. Available at https://bit.ly/3Nj8ZrL

Durkee, A. (2021) ‘Here are the Republicans most likely to refuse the COVID-19 vaccine, poll finds,’ Forbes, 28 July. Available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/alisondurkee/2021/07/28/here-are-the-republicans-most-likely-to-refuse-the-covid-19-vaccine-poll-finds/?sh=6a79d2f735f8

Ekberg, M. (2007, May) ‘The parameters of the risk society: a review and exploration,’ Current Sociology, 55(3), pp.334-366.

Emadi, A. (2020) ‘Corona: hal yajib an nakhāf minhu?’ Asharq, 12 March. Available at https://bit.ly/3QFuO7M

Emirates News Agency (2020, January 29) ‘UAE announces first case of novel coronavirus’. Available at https://wam.ae/en/details/1395302819532

Emirates News Agency (2020, August) ‘15 alf mutaṭawi‘a min 107 jinsiyāt ta‘aysh bi-dawlat al-’imārāt yushārikūna fī tajārib COVID-19 ghayr al-nashiṭ’. Available at https://wam.ae/ar/details/1395302861999

Flamerzi, I. (2020), “Al-ab‘ād al-mustaqbaliya li-Corona” Asharq, April 7, 2020, https://bit.ly/3nvC8pn

France 24 (2020), ‘Qatar: taṭbīq li-ta‘aqqub firus wasṭ jadal bisabab makhāwif muta‘aliqa bi-l-khuṣūṣiya’ Corona [Qatar: Coronavirus tracking app amid controversy over privacy concerns], May 25, 2020, https://bit.ly/3b5kF3U

Giddens, A. (1990) The consequences of modernity, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Giddens, A. (1999, January) ‘Risk and responsibility,’ The Modern Law Review, 62(1), pp.1-10.

Hamza, M. (2020) ‘Al-amn al-ṣiḥḥiyy al-waṭanī,’ Al Riyadh, 21 May. Available at https://www.alriyadh.com/1822304

Hashemi, A.S. (2020) ‘Corona wa-i‘ādat i‘mār al-‘ālam,’ Al-Ittihad, 16 December. Available at https://bit.ly/3u1CW8T

Hilabi, F. F. (2020) ‘Sīkūlūjiyat al-khawf min al-wibā’,’ Al Raya, 8 March. Available at https://bit.ly/3QJpv7b

Hosani, F. (2021) ‘Aghlib al-iṣābāt al-jadīda bi-Corona min ghayr al-muṭa‘amīn,’ Al-Ittihad, 6 May.

Ishaq, I. (2020) ‘Al-taṭawwūrāt bi-l-jā’iḥa ilā ayna?’ Al Raya, 30 December. Available at https://bit.ly/3HLE1Hu

Ishaq, M. (2021) ‘Corona Ramaḍāniya,’ Al Raya, 11 April. Available at https://bit.ly/3u0pIcG

Jansen, T. et al. (2019) ‘Understanding of the concept of ‘uncertain risk:’ a qualitative study among different societal groups,’ Journal Of Risk Research, 22(5), pp. 658-672.

Jasmi, S. (2020) ‘Jaysh al-imārāt al-abyaḍ sanad li-l-jamī‘a,’ Al Khaleej, 12 May. Available at https://bit.ly/3bpocKH

Jasmi, S. (2021) ‘Min ḥarb al-kamāmāt ilā ḥarb al-laqāḥāt,’ Al Khaleej, 19 January. Available at https://bit.ly/39J1Ao5

Jasmi, S. (2021) ‘Shā’i‘āt Corona tafakkuk al-mujtama‘,’ Al Khaleej, June. Available at https://bit.ly/3nb0unR

Jasmi, S. (2021) ‘Riyādat al-imārāt ‘ālamīyyan,’ Al Khaleej, 7 December. Available at https://bit.ly/3bcYoBe

Jassem, A. (2020) ‘La-nataḍarra‘a li-l-khāliq wa nuṣallī li-yarfa‘a ‘annā hadha al-balā’,’ Al Raya, 7 April. Available at https://bit.ly/3Oiz1g6

Kaabi, J. (2020) ‘Al-mas’ūliya al-jinā’iya ‘an naql firūs corona,’ Al Raya, 25 May. Available at https://bit.ly/3HLGfXv

Khashaiban, A. (2020) ‘Al-firūs aladhī ṭaraḥu al-as’ila al-siyāsiya amām al-niẓām al-‘ālamī,’ Al Riyadh, 13 April. Available at https://www.alriyadh.com/1815647

Kuwari, R. (2021) ‘Iltizām bi-l-kamāma wājib waṭanī,’ Asharq, 8 February. Available at https://bit.ly/3NfvZb5

Kuwari, K. (2021) ‘Likay nūwajih al-jā’iḥa min jadīd,’ Al Raya, 29 March/ Available at https://bit.ly/3xHThRe

Lash, S. and Wynne, B. (1992) ‘Introduction’ Risk society: towards a new modernity, Ulrich Beck, London: Sage Publications Ltd, pp.3-8.

Lynch, M. (2020, April) ‘The COVID-19 pandemic in the Middle East and North Africa,’ POMEPS Studies, 39, Washington, D.C., pp.3-6.

Makki, Y. (2020) ‘Corona mā ba‘dahu laysa mā qablahu,’ Al Khaleej, 3 March. Available at https://bit.ly/3OB1TQy

Makki, Y. (2020) ‘Firus corona ṭabī‘ī am muṣanna‘,’ Al Khaleej, May. Available at https://bit.ly/3OAZOUz

Makki, Y. (2020) ‘‘Ālam mā ba‘d Corona,’ Al Khaleej, 4 August. Available at https://bit.ly/39LMqym

Meza, D. (2020) ‘In a pandemic are we more religious? Traditional practices of Catholics and COVID-19 in Southwestern Colombia,’ International Journal of Latin American Religions, 4(2), pp.218-234.

Mohannadi, A. (2020) ‘Krūniyāt,’ Asharq, 27 April. Available at https://bit.ly/3HR8MuW

Mohannadi, A. (2020) ‘Ukdhūbat Corona,’ Asharq, 19 October. Available at https://bit.ly/3QLRxyU

Morished, S. (2020) ‘Naḥwa amn waṭanī biyūlūjī mutakāmil,’ Al Riyadh, 12 April. Available at https://www.alriyadh.com/1815453

Mulla, S. (2020) ‘Khubirā’ wa-fuqahā’ zaman Corona,’ Asharq, 9 April. Available at https://bit.ly/39RUy0g

Mythen, G. (2005). ‘Employment, individualization and insecurity: rethinking the risk society perspective,’ The Sociological Review, 53(1), pp.129-149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2005.00506.x

Mythen, G. (2007, November) ‘Reappraising the risk society thesis: telescopic sight or myopic vision?’ Current Sociology, 55(6), pp. 771-926.

Naeem, M. (2020) ‘‘Ālam mā ba‘d Corona: al-taqniya fī muwājahat al-bashar,’ Al Riyadh, 16 May. Available at https://www.alriyadh.com/1821422

National Emergency Crisis and Disasters Management Authority (2020) Mustajidāt fairus Corona al-mustajid (COVID-19) fī dawlat al-imārāt al-‘arabiya al-mutaḥida. Available at https://covid19.ncema.gov.ae/

Nuaimi, S. (2020) ‘Al-ḥajr wa-l-‘azl fi-l-sunnah al-nabawiya,’ Al-Ittihad, 12 May. Available at https://bit.ly/3Onm2tx

Nuaimi, S. (2020) ‘‘Ālam mā ba‘d corona,’ Al-Ittihad, 3 August. Available at https://bit.ly/3tTGQAE

Nuaimi, S. (2021) ‘Corona wa-l-irhāb al-taknūbiyūlūjī,’ Al-Ittihad, 17 May. Available at https://bit.ly/3Om0w8G

Nuaimi, S. (2022) ‘Al-niẓām al-‘ālamī mā ba‘d al-jā’iḥa,’ Al-Ittihad, 18 January. Available at https://bit.ly/3OuS9r6

Obaidan, A. (2022) ‘Al-jur‘a al-rābi‘a wa mādha ba‘d?’ Asharq, 3 April. Available at https://bit.ly/3tYUEd4

Otaibi, A. (2020) ‘Corona: al-mas’ūliya wa-l-wa‘ī,’ Al-Ittihad, 22 March. Available at https://bit.ly/3OHkiLD

Pew Research Center (2021, January 27) More Americans than people in other advanced economies say COVID-19 has strengthened religious faith. Available at https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/01/27/more-americans-than-people-in-other-advanced-economies-say-covid-19-has-strengthened-religious-faith/

Qatar Ministry of Public Health (no date) Mu‘adalāt al-taṭ‘īm bi-laqāḥ firus corona fī Qaṭar. Available at https://bit.ly/3zIqVJ1

Rashid, A. (2020) ‘Alam jāmiḥ ḥaqqan,’ Okaz, 27 March. Available at https://www.okaz.com.sa/articles/authors/2016964

Reuters (2020, February 29) ‘Qatar reports first coronavirus case in man who returned from Iran’. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-health-qatar-idUSKBN20N0IB

Rossi, T. and Kabbani, N. (2020, April 30) ‘How Gulf states can lead the global COVID-19 response,’ Brookings, https://brook.gs/3nadASD

Saad, I. (2020) ‘Al-taṭawwu‘ jaysh iḥtiyāṭī,’ Asharq, 24 March. Available at https://bit.ly/3ODO7fO

Saad, I. (2020) ‘Qatar lā tastaḥaqu minkum hadhihi al-khiyāna!’ Asharq, 28 June. Available at AT3_5eBIxau1PPGX9JEZW4pGD_y8zs5x5xmIppVdRRNmVmV2ySmlv4p6Dan7Om9jOfdBaQ8yuw2wlUSz31aaeEYkZ9mi0o2Gt0ShHI5xOOImR2gMDv5LhafyNBFDUEy1AbpvsB9uQ38hAApV__QmQw

Saati, A. (2020) ‘Tawāqimunā al-ṭibbiya khatt al-difā‘ al-awwal,’ Al Eqtisadiah, 26 April. Available at https://www.aleqt.com/2020/04/26/article_1813791.html

Saudi Center for Government Communication (2022, January 15) Imtidādan li-ḥamlatay ‘kullunā mas’ul’ wa ‘na‘ūd bi-ḥadhir” al-tawāṣsul al-ḥukūmī yutlaqu al-huwiya al-jadīda ‘manā‘atunā ḥiyāt’ ma‘a wizārat al-ṣihḥiya. Available at https://cgc.gov.sa/ar/node/625

Saudi Ministry of Health (2020, March 2) MOH reports first case of coronavirus infection. Available at https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/News/Pages/News-2020-03-02-002.aspx

SEHA (2020, December 3) Al-‘āmilūna fī khatt al-awwal yujaddidūna isti‘adādahum li-l-taḍḥiya min ajl raf‘at al-imārāt. Available at https://bit.ly/3b9viTu

Shahwani, M. (2021) ‘Kayf ta‘āmala al-rusūl ma‘a al-wibā’?’ Asharq, 24 March. Available at https://bit.ly/3QJy41V

Shaiba, A.M. (2020) ‘Lā tashalūn hum: maḍāmīn wa-risā’il,’ Al-Ittihad, 22 March. Available at https://bit.ly/3tWRIOa

Shamrani, A. (2020) ‘Waṭanunā yataṣaddī li-Corona,’ Okaz, 22 March. Available at https://www.okaz.com.sa/articles/authors/2016157

Shamsi, M.M. (2020) ‘Corona wa ḥadāratunā al-islāmiya al-‘aẓīma,’ Al Raya, 19 April. Available at https://bit.ly/3tYuBmu

Sulaiman, K. (2021) ‘Tajribatī ma‘a bilād ijtāḥathā Corona,’ Okaz, 11 November. Available at https://www.okaz.com.sa/articles/authors/2087804

Sulaiti, A. (2021) ‘Min al-wāqi‘ iḥālat al-ashkhāṣ li-l-niyāba li-‘adam labsihum al-kamāma,’ Al Raya, 15 February. Available at https://bit.ly/3HRhhWD

Suwaiji, A. (2021) ‘Corona wa-l-siyāsa,’ Al Khaleej, 12 July. Available at https://bit.ly/3bonptr

Talib, H.A. (2020) ‘Majlis al-amn al-ṣiḥḥiyy al-‘ālamī,’ Okaz, 13 March. Available at https://www.alriyadh.com/1822304

Talib, H.A. (2020) ‘Corona tahzimu ‘uqdat al-tafawwuq’ Okaz, 20 March. Available at https://www.okaz.com.sa/articles/authors/2015980

Tavares, L.M.B. and Barbosa, F.C. (2014) ‘Reflections on fear and its implications in civil defence actions,’ Ambiente & Sociedade, 17(4), pp.17-34.

Tunaiji, N. (2020) ‘Dūrūs min al-jā’iha,’ Al-Ittihad, 19 June. Available at https://bit.ly/3zZywDe

Turak, N. (2020) ‘First Middle East cases of coronavirus confirmed in the UAE,’ CNBC, 29 January. Available at https://www.cnbc.com/2020/01/29/first-middle-east-cases-of-coronavirus-confirmed-in-the-uae.html

UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation (2020, March 18) Ṣāḥib samū Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed: dawlat al-imārāt ittakhadhat ijrā’ātahā al-waqā’iya wa-tadābīrahā mubakkaran li-muwājihat firus corona. Available at https://www.mofaic.gov.ae/ar-ae/mediahub/news/2020/3/18/18-03-2020-uae-fight

Wabel, M. (2020) ‘Kullunā mas’ul,’ Al Riyadh, 11 April. Available at https://www.alriyadh.com/1815265

Wimmer, J. and Quandt, T. (2007, February) ‘Living in the risk society: an interview with Ulrich Beck,’ Journalism Studies, 7(2), p. 337.

Yamani, N. (2020) ‘Wa nabalūkum bi-l-sharr wa-l-khayr fitna, Okaz, 16 March. Available at https://www.okaz.com.sa/articles/authors/2015296

Contact us

Become a contributor