THIRD EDITION

Shujaat Ahmadzada

Northern Ireland conflict: From the past to the present

Abstract:

The conflict in Northern Ireland has been a significant cause of instability and the loss of hundreds of innocent lives. The prominence of religious identities may mislead many people to conclude that the conflict is about religion. However, the central element of the disagreement between the political segments is the constitutional status of the territory. Although the conflict itself has deep historical roots dating back to the early attempts to colonise the island centuries ago, it had been more widely discussed in the world after the eruption of street combats in Northern Ireland in the late 1960s, i.e., the Troubles period. This paper examines how a power-sharing structure is formed in Northern Ireland after decades-long armed conflict by giving descriptive historical information and providing readers with the details of the power-sharing system’s work.

Keywords: Northern Ireland; Ireland; the United Kingdom; Consociation; Conflicts.

Who is who?

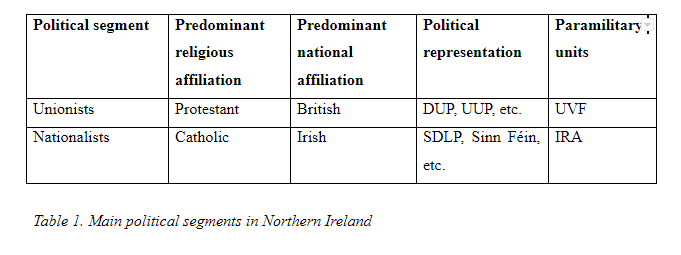

The society of Northern Ireland is not only divided along ethno religious lines, but also political positions. Table 1 shows two main conflicted segments of the region’s political future.

As it can be seen from the Table, the conflict is between the Unionists (oranges), who favour preserving the status of Northern Ireland as part of the UK, and the Nationalists (greens), who favour the unification of Northern Ireland with the rest of Ireland. The historical narrative is framed mainly by the nationalist to describe the conflict as a struggle between the Protestant majority and Catholic minority, although data shows no significant demographic differences between Protestant and Catholic communities (NISRA, 2011).

In addition to the two main segments of the conflict, several other stakeholders also have had a say in the conflict. The United Kingdom’s role is of particular importance, and despite the correlation between London’s and the unionists’ positions, the UK tried to remain neutral. This neutrality nonetheless had not been accepted by both communities sincerely: on the one hand, nationalists continued to see the British government as a herald of colonialism, while many unionists saw the UK’s position as a betrayal towards their historical struggle (International Alert, 2014). Similarly, the Republic of Ireland has remained neutral, although the island’s division as a historical injustice has always been a narrated way of the conflict there.

Overall, two factors shaped the policy of the United States towards the conflict and have led to an equilibrium in the foreign policy alliance with the United Kingdom (English, 2007: 237). First the UK urged the US not to support any step that would threaten its territorial integrity. The second concerns the Irish diaspora in the United States and their influence on the conflict.

Historical Background: 851 years

A typical nationalist narrative could help to explain the conflict from 1169, when the first Anglo-Norman tribes started to settle on the island. This fact may be irrelevant for the current order of international relations, but one should not forget the particular role of migration to the island throughout history nonetheless. Following the Reformation in England, new settlers were mainly Protestants. Compared to the traditional Celtic communities, they had more material and political resources, because the colonial power protected their existence vigorously and provided them with access to more fertile lands and natural resources. Furthermore, inequality of distribution of resources had weakened the clan-based structures of Celtic communities vis-à-vis Protestants and exacerbated the segregation among them.

The Great Famine, caused by the potato disease between the years 1845-1848, claimed the lives of thousands of people and resulted in the departure of thousands more from the island (mainly ancestors of the Irish diasporas worldwide today). However, the primarily peasant Celtic communities suffered more, and this purely natural phenomenon turned into a common tragic footprint in the Celtic identity. Even today, this calamity, which took place 171 years ago, remains one of the nationalists’ main arguments in their struggle against British rule (International Alert, 2014).

Today’s political fragmentation also has an economic background. The primary income of those who lived in the northern parts of the island (current Northern Ireland) came from trade with Britain. As a result, they needed a sizeable British market to make more money (McCartney, 2014). Nevertheless, in the rest of the island, the economy was based mainly on agriculture, and the influx of cheaper, better-quality British products resulted in the loss of the domestic market. In other words, unlike the North, elites of the rest of the island wanted to have a “distance,” i.e., autonomy, from Britain (McCartney, 2014).

It is quite paradoxical that the United Kingdom was the one that further exacerbated the idea of Irish independence by imprisoning and executing Irish rebels during the Easter Uprising of 1916. On the one hand, the Irish accepted it as a sign of humiliation, and that turned into a myth of national revival. On the other hand, Britain considered rebellion as a sign of stabbing back during the First World War (Zolyan, 2017: 16). The struggle for Irish independence turned into a civil war and ended in signing the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, which divided Ireland into two parts: Northern Ireland, where Protestants were the majority and Catholics were the minority, and the present-day Republic of Ireland. Both communities of Northern Ireland experienced a security dilemma after the division: Protestants saw themselves as a minority on the island of Ireland and believed Catholics were trying to unify the island and assimilate them. Concurrently, Catholics saw themselves as a minority within Northern Ireland, divided as a result of the historical injustice.

In the 1960s, Catholic community members called for equal rights after decades of marginalisation, drawing inspiration from the US civil rights movement. The call for equal rights was perceived as a call for unification by the Protestant community and provoked street clashes. British troops were deployed in the region in 1969 to maintain control (CAIN, 2020). The civil organisations’ incompetence in defending citizens’ rights created a vacuum, and paramilitary organisations soon filled this gap (McEvoy, 2008: 32).

Though there were various peace initiatives during the street battles, also known as the Troubles period, they often failed (for example, the 1974 Sunningdale Treaty). The main reason for their failure was that all sides believed in their ‘power’ and saw power as an alternative to peace. Gradually, however, from the 1990s onwards, both the UK and paramilitary groups realised that it was impossible to win street battles, not from a military-technical point of view, but because the more violence meant more casualties and war fatigue reached its peak.

As a result of formal and informal negotiations, the parties involved in Northern Ireland’s political life began multi-party talks in 1996. The Belfast Agreement, known as the Good Friday Agreement, was signed on April 10, 1998, thus ending the violent conflict in Northern Ireland. It consisted of two separate deals: the multi-party agreement by political parties in Northern Ireland and the British and Irish governments; the British-Irish agreement signed between the British and Irish governments.

How is Northern Ireland governed?

The Belfast Agreement reaffirmed that Northern Ireland was a self-governing region within the United Kingdom. However, both the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom recognised the right of the people of Northern Ireland to change their constitutional future by achieving inter-communal consensus, i.e., right to self-determination (Morgen, 2000: 43).

Today, Northern Ireland has a system of governance based on inter-communal consensus, and all decisions about the future of the region must be made jointly by either direct or indirect representation of two political segments. Public participation in the region’s governance is implemented through elections to local councils, the Northern Ireland Assembly, and the UK Parliament. The liberal consociation nature of politics creates an opportunity for constituents to vote for their own ideological/ethnic parties, although they are not required to do so (O’Leary, 2005: 16).

The Northern Ireland Assembly (Stormont) is an elected legislative body comprising 90 members known as the Members of Legislative Assembly (MLAs), and those MLAs are obliged to designate themselves either as “nationalist” or “unionist” to ensure political participation of both segments in the Assembly (NI Assembly, 2020).

One of the main elements of the consociational governance in Northern Ireland is the veto power of political parties in the Assembly over each other. That element is called the cross-community voting principle: that principle applies for the appointment of the Speaker and Deputy Speakers of the Assembly, over financial and budget issues, and on any other issue if a minimum of 30 MLAs calls for it. Cross-community voting could be done in two ways: 1) parallel consent – the majority of Nationalists and Unionists have to agree (Scheckener, 2002: 221); 2) weighted majority – 60% of all present MLAs and at minimum 40% of each side have to agree.

The Northern Ireland Executive is an administrative branch of the Assembly and consists of the First Minister, the Deputy First Minister, and eight other ministers with various portfolios. The executive governance of Northern Ireland has the nature of a diarchy as the First Minister and the Deputy First Minister have the same executive powers, although the name differentiation suggests that the Deputy First Minister is subordinate to the First Minister.

While the First Minister and the Deputy First Minister are nominated separately by the largest parties in each of the political segment in the Assembly, the allocation of the rest of the ministers (except for the Minister of Justice) takes place by using a unique algorithm called the d’Hondt formula, which excludes political parties that failed to achieve significant levels of electoral support (O’Leary, 2005: 15). The Minister of Justice, however, is elected by a cross-community vote due to the sensitive nature of the portfolio.

Each ministry is linked with the Assembly’s respective committee, which can initiate the draft laws, thereby ensuring checks and balances. Ministries ought to defend their policy initiatives before the respective committees. Moreover, the Special Committee in the Assembly is responsible for checking each draft of laws initiated by the executive body on human rights (Scheckener, 2002: 223).

The Belfast Agreement also established the cross-border bodies: “The North/South Ministerial Council”, which acts to coordinate activities between the Governments of Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland; and “The British–Irish Intergovernmental Conference”, which acts to coordinate activities between the Governments of the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom (Kenny, 2018).

Why was Northern Ireland successful?

The power-sharing system established in Northern Ireland is an example of liberal consociationalism combined with territorial autonomy (O’Leary, 2005: 34). In this section, the variables that led to the formation of consociational governance in Northern Ireland will be discussed using an inductive approach.

First, the relative equilibrium in the two communities’ demographics in Northern Ireland played a significant role in forming power-sharing bodies (Schneckener, 2002: 211). As a result of the demographic change in the 1970s and 1980s, Protestant and Catholic communities became equal in size, and that blurred the traditional narrative of ‘struggle between the Protestant majority and the Catholic minority’. In 1971-1991, the Catholic community saw an increase from 33% to 40%, which shook the dominant stance in the unionist segment’s mindset (Boyle, 1994: 30-33).

Additionally, the small demographic size of the region has facilitated the establishment of consociational formation. The phrase “great hatreds, little room” by William Butler Yeats, an Irish poet of the 20th century, is a poetic expression of this variable (O’Leary, 2005: 31). The small demographic size, in combination with the demographic shift in the last five decades, made political segments sure that it was almost impossible to change the power balance through the street battles. As Adriano Pappalardo notes, “consociational democracy is a pact among minorities who are not in a position to change the existing distribution of power” (1981: 365).

The elimination of socio-economic differences between communities also positively affected the formation of a consociational structure (Schneckner, 2002: 211). In particular, with the accessions of the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland to the European Economic Union in 1973, this process became more apparent and in 1983 the “International Fund for Ireland” was established. Moreover, the European Union alone has allocated 708 million euros to contribute to people’s coexistence affected by the conflict in Northern Ireland (Pashayeva, 2014). The UK government has also implemented several investment programmes to reduce inter-communal socio-economic disparities in Northern Ireland.

The position of the United Kingdom has made a significant contribution to the peaceful transformation of the conflict too. The existence of independent judiciary and democratic institutions has led to the investigation of crimes even in times of public emotional height. Moreover, the imprisoned nationalists’ election to the UK parliament brought a great deal of prestige to the paramilitary groups. They appreciated the benefits of political fame and gradually renounced violence to remain on the political agenda. The same was true of unionists: the UK arrested them, and the ‘shock therapy’ of being arrested by a country they fought for made them question the very postulates of unionism ideology.

Besides, the change in the nature of the political forces in Northern Ireland had a say in the peace process. In the 1970s, parties representing both political segments fell into the abyss due to intra-party issues and became politically fragmented, which further increased political instability and decreased coalition formation. However, in the 1990s, the multi-party situation in Northern Ireland became consolidated and more parties were able to negotiate with each other without the fear of being blackmailed by others; as Lijphart argues, “political fragmentation normally increases the ‘blackmail potential’ and decreases the ‘coalition potential” (1977: 65).

Finally, the most critical element that facilitated the peace process and made it successful after the failure of the peace attempt in 1974 (Sunningdale) was the inclusion of all stakeholders in the political conflict to the process in the multi-party talks of 1996-1998 (Schneckener, 2002: 211). Peace could not be achieved in 1974 due to absence of communications with the paramilitary groups that were the main cause of the violence, but in the last peace attempt, even such contacts with IRA militants who committed terrorist acts were established by official institutions of the United Kingdom.

Conclusion

In sum, the study of the Northern Ireland conflict is of particular importance for examining how violent conflicts can be transformed peacefully and how consociational governance can be established in post-conflict communities. This conflict is one of the few examples in the world where peaceful negotiations were able to end violence (International Alert, 2014).

The study of this conflict also helps us take a position in the debates on such power-sharing processes in political academia by observing one of the rare practical applications of consociationalism theory. It is important to remember that political analysts who oppose the conflicts’ consociational settlement have always argued that such systems are undemocratic in nature. In their opinion, consociational political arrangements deepen existing wounds rather than closing them and make these differences a daily norm (Lijphart, 1977).

On the other hand, proponents of consociation theory take these criticisms for granted and put themselves in a more realistic position. Indeed, to take concrete steps in regulating conflicts, it is sometimes necessary to institutionalise, or more precisely formalise, the differences that have already been accepted as the daily norm. As O’Leary argues:

“They [consociationalists] believe that certain collective identities are generally durable once formed, however, to say that they are durable does not imply that they necessarily generate intense throat-cutting antagonisms” (2005: 8).

Given these realities, in Northern Ireland, the parties decided to institutionalize their differences and end the street fighting. This allowed political groups in Northern Ireland to have a more significant say in distributing public resources through dialogue, and in return, prevented human suffering.

Despite all these positives, it is a fact that today, inter-communal trust in Northern Ireland has not been fully restored and society is still largely segregated. In particular with Brexit, the fragile pillars of peace that had remained steady for nearly a decade were shaken again, and this in itself sparked many debates. This proves that more needs to be done to achieve Galtung’s positive peace – lasting peace that is built not only by institutions but also by societal attitudes (Galtung, 1996), to preclude the emergence of a spontaneous spark that can destroy all the work done so far.

Boyle, K., Hadden, T. (1994), Northern Ireland: The Choice, London: Penguin.

CAIN: Chronology of the Conflict, https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/othelem/chron/ch68.htm, [Accessed November 12 2020]

Central Statistics Office, https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/er/pme/populationandmigrationestimatesapril2018/, [Accessed November 21 2020]

Cochrane, F. (2013), Northern Ireland: The Reluctant Peace, New Haven, and London: Yale University Press.

English, R. (2007), Irish Freedom: The History of Nationalism in Ireland, London: Pan Books.

Galtung, J. (1996), Peace by Peaceful Means: Peace and Conflict, Development and Civilisation, Oslo: PRIO.

Kenny, J. (2018), ‘The Good Friday Agreement: A brief guide’,

https://www.bbc.com/news/av/uk-northern-ireland-43706149, [Accessed on 2 December 2020]

Hasanov, A. (2014), ‘The society of Northern Ireland in search of peace’, International Alert, pp. 64-71.

Lijphart, A. (1977), ‘Democracy in Plural Societies’, New Haven: Yale University Press.

McCartney, C. (2014), ‘How did we end up in this situation?’, International Alert, p. 6-13.

McEvoy, J. (2008), The Politics of Northern Ireland, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Morgen, A. (2000), The Belfast Agreement: a practical legal analysis, London: The Belfast Press.

Northern Ireland Assembly,

https://education.niassembly.gov.uk/post_16/snapshots_of_devolution/gfa/designation, [Accessed November 12, 2020]

Northern Ireland Executive, https://www.northernireland.gov.uk/topics/executive-documents, [Accessed November 15, 2020]

Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, http://www.ninis2.nisra.gov.uk/public/Theme.aspx?themeNumber=136&themeName=Census%202011, [Accessed December 02, 2020]

Office for National Statistics, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates, [Accessed November 23, 2020]

O’Leary, B. (2005), ‘Debating Consociational Politics: Normative and Explanatory Arguments’, in S. Noel (ed.) From Power Sharing to Democracy, Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Pashayeva, G. (2014), ‘The role of official diplomacy and foreign actors in settlement of the Northern Ireland conflict’, International Alert, pp. 25-37.

Schneckener, U. (2002), ‘Making Power-Sharing Work: Lessons from Successes and Failures in Ethnic Conflict Regulation’, Journal of Peace Research, pp. 203-228.

Yeats, W. (2008), The Collective Poems of W.B. Yeats, New York: Scribner Paper Fiction.

Zolyan, M. (2014). ‘From bombs to bulletins: political institutions and the transformation of the conflict in Northern Ireland’, International Alert. pp. 14-24.

Contact us

Become a contributor