FIRST EDITION

VOL TWOVictor Mulsant

Mapping out the Dynamics of Conflicting Socio-political Narratives and their Sources of Legitimacy

Abstract

In any given societal structure, actors compete over which narrative should be mainstream and dominate the public sphere. This paper seeks to establish a model that explains the power relations and dynamics between the various actors of narrative dominance. Building on this, the paper attempts to evaluate the two main categories of sources of narrative legitimacy: structural and theoretical. Structural sources are authority, and the challenging of authority. Theoretical sources are truth and morality. The paper concludes that while crucial, the asymmetrical conditions of power do not inherently define what narrative will be accepted by the target audience, as theoretical sources of legitimacy must not be underestimated.

Key words: Conflicting narratives, asymmetrical relations of power, narrative legitimacy

Introduction

In the beginning of 2003, millions marched to oppose the possibility of their countries going to war against Saddam Hussein. In the United Kingdom specifically, the public sphere found itself partitioned between the pro and anti-war movements, the pro-war movement being supported by Tony Blair’s government. A lot was written about the conflicting roles of media actors in the run-up to the war (Robinson, 2010). The pro-war media proposed a narrative of fighting terrorism and dictatorship, putting an end to the ruthless rule of the autocrat and establishing a democracy. The anti-war movement rejected the baseless conception that Iraq possessed Weapons of Mass Destructions (WMDs) and argued that any invasion would result in the loss of thousands of lives of innocent civilians. This specific case is actually a counterexample: while the overall British target audience rejected the narrative proposed, the UK went to war regardless (Elliott, 2016). However, in most democracies, governments tend to follow public opinion, regardless to the extent to which they shape it (Burstein, 2003). Hence, the narrative that ends up dominating the public sphere is likely to be the one determining public policy.

To understand the power dynamics and struggles that exist between competing narratives, and how legitimacy revolves around them, one first needs to understand what a narrative is. While the word is well known, the extent of its signification is much less so. Mayer (2014) says narratives are ‘stories’ that humans are hungry for. Wibben (2010) argues narratives are the framework we build to share a common conception of the world. Patterson and Monroe (1998) say they are both. Barthes and Duisit (1975) talk about an ‘[infinity of forms]’. Narratives are stories, frameworks, ways of viewing and conceiving the world. They enlarge our understanding of things, but also restrict it (Wibben, 2010). They can be rooted in historical events or shaped by values; the one thing that is common for all of them is that they are crucial to the lives of the people that concern them.

In order to understand the extent to which competing narratives in asymmetric positions of power are equally legitimate, one first needs to understand how narratives compete with each other, and how asymmetric relations of power are created in the process. This paper will consider in the first part how narratives gain or lose legitimacy by considering various case studies and theoretical arguments. In the second part, it will argue that there are two different types of sources of legitimacy for narratives: structural and theoretical. This paper will argue that the legitimacy of narratives depends more on the intrinsic ability of narratives to convince the audiences rather than the asymmetric conditions of power.

Part 1: Mapping competing narratives

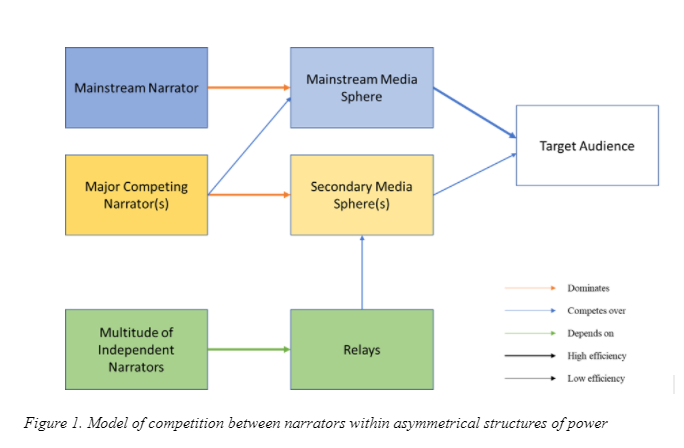

In any given system of competition between narratives, there is a dominant narrator, an authority. In a typical national setting, this will be a government. In the case of pre-Iraq War United Kingdom, this was Tony Blair’s government. The authority, as the mainstream narrator (MN), dominates the mainstream media sphere (MMS). This is what academics like Gramsci and Foucault have defined as the ‘hegemony’ (Molden, 2016). This is also what schools of securitisation refer to as macro-securitisation (Buzan and Wæver, 2009). Essentially, it is the established mainstream understanding of the conceptualisation of narratives and their logic. Here, the mainstream media sphere is not just the accumulation of media platforms but rather the intangible web of knowledge sharing that validates narratives. Within the MMS dominated by the narrative of the rightfulness of the War on Terror and the necessity of the fight against the Axis of Evil, the narrative of cooperation between Iraq and Al-Qaida can be validated even though it is not factual. To some degree, the MMS is the reflection of the extent to which an idea or a narrative is commonly accepted, particularly by the elite that has the capacity to turn narratives into action. The MMS not only reflects the narrative pushed forward by the MN but also, although less so, the narratives of the major competing narrators (MCNs, see Figure 1). While the MCNs only challenge the superiority of the mainstream narrator’s narrative inside the mainstream media sphere, they usually dominate secondary media spheres (SMSs).

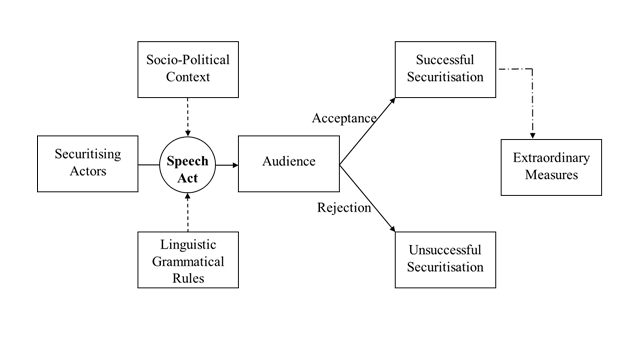

SMSs are webs of knowledge sharing which are not dominated by the mainstream narrator, they are numerous and diverse. Their diversity reflects the accumulation of many narratives emerging from a multitude of independent narrators (INs) through relays (See Figure 1). The relays can also be diverse in their nature, but they usually are both formed by and support the narratives of NGOs, activists, and knowledge groups (Herath, Schulz and Sentama, 2020). Essentially, the media spheres are the platforms through which the different narrators attempt to convince the audience of the superiority of their narrative. The nature, scope and power of audiences can vary. An audience can be the entire population, the voting population, or an elite in power at some level. Indeed, it happens that non-majoritarian narratives are maintained as dominating because of their targeting of powerful elites, just like the Apartheid in South Africa remained the dominating narrative despite it only being accepted by a fraction of the population. The processes used by narrators within the media spheres are comparable to the Copenhagen School of securitization’s concept of speech acts as securitizing methods: the different narrators, within media spheres, use speech acts to convince an audience of the superiority of their narrative. It could be argued that this understanding of audiences assumes their homogeneity. However, what it actually argues is that the composition and diversity that can exist within audiences does not matter so long as the audience accepts or rejects a narrative. Identitarian factors may very well define whether particular groups within the audience will reject or accept a narrative, however this paper leaves to public opinion studies the role to explain why they would do so, and how audiences altogether chose.

The competition model clearly highlights the structural and asymmetrical power differences between the narrators. The MN is advantaged since its narrative will systematically be favoured by the MMS and thus more intensely heard and accepted by the audience. To a lesser extent, so are MCNs. However, the game is rigged against independent narrators that not only must rely on the support of relays but also are disadvantaged by smaller coverage. Yet, there can never be a definitive winner of the game. Besides, the model is limited in that a new version must be conceptualised for each audience. There will always be larger and smaller audiences for which the actors will change.

For instance, within Israel, the Israeli government and Parliament are the mainstream narrator and support a narrative in which the occupation of Palestine is legitimate, legal, and non-harming (Burrell, 2003). The major competing narrators would be the Palestinian authorities (the PLO and Hamas), and arguably the Arab Israeli representatives; and independent narrators would be NGOs, private citizens’ voices and research-oriented academic networks. Even if the current narrative favoured by the Israeli audience and validated through elections may be that propagated by the government and endorsing the legitimacy of colonisation, such narrative is not ensured to last indefinitely, and can only be valid within the Israeli setting. The same competition of narratives within the Palestinian territories, or across the international community, will have different actors, slightly different narratives and different outcomes (Rotberg, 2006). Within the West Bank, the PLO and Hamas will act as MN instead of MCN and are likely to dominate the local MMS.

Part 2: Sources of narrative legitimacy

We have determined how narratives systematically find themselves in asymmetrical conditions of power. Are they then systematically unequally legitimate? To answer this question, one must find out how narratives become legitimate. This paper argues that there are two different kinds of legitimacy affiliated to narratives: the first one is structural, and the second kind is theoretical.

Building on Bourdieu’s work in their ethnography of the politics of rituals in Timor Leste, Población and Castro (2014) argue that within a given structure, narrators compete for ‘narrative capital’. While the concept of the struggle for ‘narrative capital’ is what the Competition model seeks to show, it does not insist on the inherent legitimacy of authority. Within a perpetual game of ‘authority and discredit’, Timorese narrators challenged each other to structural societal roles -honorary titles- which possess inherent legitimacy. While Población and Castro’s research focused on the role of rituals, the idea that societal hierarchy signifies a difference in narrative legitimacy is not surprising.

Based on a study of USA Congressional debates about the non-profit sector, Sobieraj (2007) concluded that US Congress members (jointly constituting the mainstream narrator) attempted to push forward a new narrative situating them in the “central and heroic character position”. They did so because they possessed the institutional capacity to take such action; and they partly succeeded in their attempt to do so because of the embedded privileges they disposed of as members of Congress. This illustrates that the mainstream narrator does not usually seek to offer viable alternatives to the audience, but rather fights the existing narrative alternatives because they oppose the mainstream narrator’s interests as the central, hegemonic actor of that polity’s governance ecosystem. If the mainstream narrator was actually interested in the wellbeing of the audience, it would not seek to limit narrative opportunities available to the audience; to the contrary, it would provide them with a viable platform.

Two key implications for the main argument of this paper emerge from this argument. Firstly, the MN does indeed seek to limit or silence alternative narrators, not just compete with them. Going back to Israel and Palestine, one can argue that the use of both physical and institutional violence against alternative narrators did lead to a loss of legitimacy of the mainstream narrative (Rouhana in Rotberg, 2006). It can be argued that being the MN did not intrinsically add legitimacy to the narrative, which may be because the mainstream narrative led to the systematic oppression of alternative narrators who did not agree with its supremacy. Yet, that is not entirely true. As argued previously, different settings of competing narratives enframe different actors and different outcomes. Although the abuse of power by the dominating MN did lead to a loss of legitimacy within the Palestinian and international narrative battlefields, this had only a slight impact within the Israeli theatre of operations (Ibid).

The second implication results from the first. As Mainstream Narrators abuse their superior power and control tools, MNCs experience definite legitimacy gains. In their study of public support for insurgencies, and examining the cases of Al-Qaïda, the Taliban, the Kurdish PKK and the Nepali Maoists, Davis and colleagues (2012) have found that , insurgencies gained legitimacy systematically because of the perceived ‘duty’ of fighting the abusive superior actor. The narrative of the freedom fighter fighting for a just cause appears to be found legitimate by audiences, but only if there is perceived abuse from the hegemonic actor.

Yet, this paper does not argue that MCNs are at an advantage against the MNs, for the sole reason of the usual significance of difference in means available. The War on Terror is probably the most suitable example. In the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attack, one tool which the MN had at its disposal but was not available to compete narrators was the domination of media spheres, particularly with visuals. The importance of images is crucial to the audience’s choosing of a narrative over another (Shepherd, 2008). We commonly say that an image is worth a thousand words; this certainly is true when it comes to shocking people. For MCNs and INs alike, contesting the visual MSs is extremely challenging. That is because while violence is easy to represent visually, peace is not. Once frightened, an audience will more easily choose a narrative of revenge over a narrative of de-escalation. This is demonstrated by the fact that the solution found by alternative narrators was not to challenge the visual violence of the tools presented by the MN but rather to show violent images of their own, committed by the MN (Ibid).

For INs, being heard is an almost impossible task during a time of crisis. To an extent, their influence over the MSs can only appear either in peaceful times or when the crisis is reaching its end point. We only hear about ‘collateral damage’ years after it happened, particularly because the collective voices of the INs could finally challenge the mainstream narrative (Gregory, 2019). It is unfortunate that the INs are muted during crises because they often are the best equipped to promote peace. Johan Galtung, the father of Peace Studies, argued that in order to build positive peace, lasting peace, justice and reconciliation were key (Galtung and Webel, 2017). Because of their nature, independent narratives often are voiced by individuals, or smaller groups of people. They are centered around individual stories and emotions, in opposition to generalisations, and their goal is usually to put an end to human suffering (Burrell, 2003). They could be linked to the concept of Human Security, in opposition to more traditional views of security (Kaldor et al, 2007).

Because of their individual-centered objective, independent narratives are often perceived to be more legitimate than their counterparts since their validity rests on the plausibility of their reality instead of an accumulation of value-systems, intergroup relations, and political agendas. An example can be the tragic death of 3-year-old Aylan Kurdi in 2015 on a Turkish shore, relayed by a photo gone viral. While the photo did not single-handedly transform migration policies in Europe, the tragedy shocked many, much more than a vague intangible conception of the phenomenon of human migration possibly could have (Greenslade, 2015). This brings us to the other source of narrative legitimacy, which this paper calls theoretical.

There are two theoretical sources of narrative legitimacy: truth and morality. Whilst clashes between narratives, especially narratives of conflicts, are common occurrences, so are moral condemnations of crimes and abuses. Given existing standards of human rights and international and national laws, one could argue that narratives defending violations will systematically lose legitimacy when clashing with narratives critical of those very violations. Garagozov and Gadirova (2019) demonstrated that even during ethnic conflicts, enemies on different sides reacted emotionally to the narratives of suffering of the opposite side, leading to a questioning of the mainstream war-prone narrative. The examples of mainstream narratives losing legitimacy because of accusations of human rights violations are numerous: the US invasion of Iraq, the US presence in Afghanistan, the NATO intervention in Libya, the genocide committed by the Myanmar military against the Rohingya population, or the systematic oppression of Uighurs in Xinjiang. But the phenomenon of legitimacy-loss goes further. In some places, indirect involvement of MNs, like the sale of weapons to partners committing atrocities may be enough to challenge the mainstream narrative, as has been seen in Europe, and particularly in Germany and the UK after allegations of crimes committed by the Saudi military against the Yemeni population (Sabbagh, 2021).

The second theoretical source of narrative legitimacy, which is particularly relevant during a pandemic like Covid-19, is truth as a norm. While one could argue that all narratives are systematically legitimate whether they be true or false because they represent the perspectives of individuals, the dissemination of false information has negatively impacted the legitimacy of the narrators responsible for this. The results of the 2020 US presidential and congressional elections may be attributable to precisely this factor (CNN, 2021). However, the reality is more complex than this. Unfortunately, truth is something hard to quantify, for discourses are often full of partial truths, lies, and silences.

Mayer (2014) demonstrates how MCNs opposing the narrative of the human causality of climate change, which is scientifically proven, have nonetheless gathered enormous capital and legitimacy within specific population groups. If one wants to use a more conflict-oriented example, the Israeli-Palestinian struggle once again provides valuable insights. Burrell tells us of Israeli audiences that reject the truth of the oppression of the Palestinian people because it would not fit their own narrative of being the victims (2003). How could one be both a victim and a perpetrator? Besides, the complexity of conflicts often makes it virtually impossible to authoritatively distinguish between objectively true and false claims. The competition of narratives over the abuse of chemical weapons in the Syrian civil war is such an example: such weapons were allegedly used by both the Syrian government and opposition forces, whilst both camps equally denied doing so. During military conflicts, figuring out the truth is even more complex, and thus its effect on the legitimacy of narratives will be limited until the conflict is resolved and the INs are in a position to effectively diffuse narratives not yet widely heard.

Conclusion

This paper’s main objective was to map out the power relationships between competing actors attempting, within a specific context, to dominate a public policy narrative. It argued that within any given political or social context, the mainstream narrator (usually powerful political institutions) dominates the mainstream media sphere, while mainstream competing narrators (either less powerful institutions, or political opposition, or elements of civil society) struggle to convince the audience to accept their narrative of the events over that of the mainstream narrator’s. At the same time, the mainstream competing narrators dominate secondary media spheres, often unaffected by the influence of the mainstream narrator. Within secondary media spheres, independent narrators attempt to generate via relays new narratives by proposing more authentic visualisations focused on individual, human stories.

Besides this attempt at mapping out such relationships, this paper aimed to explain the origins of the legitimacy of narratives. It argued that legitimacy emerges both from the possession of authority and the challenging of it. Besides, legitimacy is also the result of the perception of a narrative as being moral, or truthful. This paper is limited by its inability to consider quantitative data in order to attempt at generalising what is very much a theoretical theory of narrative power relations. It would be interesting to complement this approach by studying the factors that are prevalent in causing shifts in mainstream narratives, or the absence of shifts. Attempts should also be made to connect securitisation, public opinion and intergroup conflict studies together to both make sense of the diversity of concepts and to ascertain whether or not they are compatible in their approaches of narratives, public opinion, and change and adaptation factors. As disinformation becomes a political tool of international relations that directly impacts foreign policies and warfare, it is crucial to understand how narratives that shape public opinion and thus policy, compete and how they gain legitimacy. The difference between a narrative of security and one of compassion in how asylum seekers are regarded is quite literally a matter of life and death.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barthes, R. and Duisit, L. (1975) ‘An Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative’, New Literary History, 6(2), pp. 237–272. doi:10.2307/468419.

Burrell, D.B. (2003) ‘Competing Narratives: Philosophical Reflections on the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict’, Holy Land Studies, 2(1), pp. 73–84. doi:10.3366/hls.2003.0011.

Burstein, P. (2003) ‘The Impact of Public Opinion on Public Policy: A Review and an Agenda’, Political Research Quarterly, 56(1), pp. 29–40. doi:10.1177/106591290305600103.

Buzan, B. and Wæver, O. (2009) ‘Macrosecuritisation and security constellations: reconsidering scale in securitisation theory’, Review of International Studies, 35(2), pp. 253–276. doi:10.1017/S0260210509008511.

CNN, V.S. and J.A. (2021) Trump pollster says Covid-19, not voter fraud, to blame for reelection loss, CNN. Available at: https://www.cnn.com/2021/02/02/politics/trump-2020-reelection-loss-covid/index.html (Accessed: 2 March 2021).

Davis, P.K. et al. (2012) Understanding and Influencing Public Support for Insurgency and Terrorism. Santa Monica, United States: Rand Corporation, The. Available at: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/gla/detail.action?docID=1024324 (Accessed: 2 March 2021).

Christopher Elliott (2016) The Chilcot Report, The RUSI Journal, 161:4, 4-7, DOI: 10.1080/03071847.2016.1224487

Galtung, J. and Webel, C. (2007) Handbook of Peace and Conflict Studies. Available at: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203089163.ch1 (Accessed: 2 March 2021).

Garagozov, R. and Gadirova, R. (2019) ‘Narrative Intervention in Interethnic Conflict’, Political Psychology, 40(3), pp. 449–465. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12531.

Greenslade, R. (2015) ‘Images of drowned boy made only a fleeting change to refugee reporting’, The Guardian, 9 November. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/media/greenslade/2015/nov/09/images-of-drowned-boy-made-only-a-fleeting-change-to-refugee-reporting (Accessed: 21 December 2021).

Gregory, T. (2019) ‘Dangerous feelings: Checkpoints and the perception of hostile intent’, Security Dialogue, 50(2), pp. 131–147. doi:10.1177/0967010618820450.

Herath, D., Schulz, M. and Sentama, E. (2020) ‘Academics’ manufacturing of counter-narratives as knowledge resistance of official hegemonic narratives in identity conflicts’, Journal of Political Power, 13(2), pp. 285–304. doi:10.1080/2158379X.2020.1764813.

Jacobs, R.N. and Sobieraj, S. (2007) ‘Narrative and Legitimacy: U.S. Congressional Debates about the Nonprofit Sector’, Sociological Theory, 25(1), pp. 1–25. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9558.2007.00295.x.

Judge, A. (2021) ‘Copenhagen School Securitization Theory’. Unpublished work. University of Glasgow, Glasgow.

Kaldor, M., Martin, M., & Sabine Selchow. (2007). Human Security: A New Strategic Narrative for Europe. International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-), 83(2), 273–288. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4541698

Mayer, F.W. (2014) Narrative Politics: Stories and Collective Action, Narrative Politics. Oxford University Press. Available at: https://oxford-universitypressscholarship-com.ezproxy.lib.gla.ac.uk/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199324460.001.0001/acprof-9780199324460 (Accessed: 26 February 2021).

Molden, B. (2016) ‘Resistant pasts versus mnemonic hegemony: On the power relations of collective memory’, Memory Studies, 9(2), pp. 125–142. doi:10.1177/1750698015596014.

Patterson, M. and Monroe, K.R. (1998) ‘Narrative in political science’, Annual Review of Political Science, 1(1), pp. 315–331. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.1.1.315.

Población, E.A. and Castro, A.F. (2014) ‘Webs of Legitimacy and Discredit: Narrative Capital and Politics of Ritual in a Timor-Leste Community’, Anthropological Forum, 24(3), pp. 245–266. doi:10.1080/00664677.2014.948381.

Robinson, P. (ed.) (2010) Pockets of resistance: British news media, war and theory in the 2003 invasion of Iraq. 1. publ. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Rotberg, R.I. (ed.) (2006) Israeli and Palestinian Narratives of Conflict: History’s Double Helix. Bloomington, United States: Indiana University Press. Available at: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/gla/detail.action?docID=316179. pp 1-18 / 115-142 (Accessed: 26 February 2021).

Sabbagh, D. (2021) ‘UK authorised £1.4bn of arms sales to Saudi Arabia after exports resumed’, The Guardian, 9 February. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/feb/09/uk-authorised-14bn-of-arms-sales-to-saudi-arabia-after-exports-resumed (Accessed: 21 December 2021).

Shepherd, L.J. (2008) ‘Visualising violence: legitimacy and authority in the “war on terror”’, Critical Studies on Terrorism, 1(2), pp. 213–226. doi:10.1080/17539150802184611.

Wibben, A. (2010) Feminist Security Studies : A Narrative Approach. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203834886.

Contact us

Become a contributor